Anneliese Lederer, Director of Fair Lending

Sara Oros, Program Coordinator, Fair Housing/Fair Lending

In collaboration with:

Dr. Sterling Bone, Professor of Marketing, Utah State University

Dr. Glenn Christensen, Associate Professor of Marketing, Brigham Young University

Dr. Jerome Williams, Distinguished Professor and Prudential Chair in Business, Rutgers University

Before COVID-19, tests revealed better treatment of White applicants for small business bank loans compared to Black ones. Matched-pair tests revealed similar disparities for PPP loan applicants.

Executive Summary

Since March 2020, businesses in the U.S. have been struggling to continue operations in the face of a global pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a recession because of the widespread closures of non-essential businesses enacted to reduce the spread of the virus. Even as things begin to reopen, people are less likely to go out due to possible health risks. In response, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act which created the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). The PPP is a lending program that provides money, in a potential grant format, to small businesses to help them weather the economic effects of the pandemic. The majority of the loan needs to be allocated for employee salaries and then the remainder can be used for other business expenses like rent and loan payments. The purpose of this study was to determine whether the disparities in small business lending we have detected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic continued with implementation of the PPP program.

There have been problems with the implementation of the PPP as there were concerns that the banks were initially primarily working with current clients and prioritizing their larger clients over smaller clients so that they could receive larger processing fees. In addition, the Small Business Administration (SBA), for at least the beginning phase of PPP, did not collect borrower demographic information so there was little information available regarding who actually received loans or if businesses received the full funding they requested.

In part, because of these data limitations, the role of lending discrimination in the allocation of the PPP funding has not been fully studied. The National Community Reinvestment Coalition, in collaboration with our academic partners, conducted matched-pair audit testing of financial institutions in Washington, DC. Matched-pair testing is a method used to detect discrimination by using a pair of testers with different races (or other protected class) but similar profiles as a way to determine differences in treatment from financial institutions. This testing, where Black and White applicants with similar credit characteristics applied to a lender in the same time period, was a continuation of the work that we conducted in 2017, 2019 and earlier in 2020 related to discrimination in small business lending. The matched-pair testing provides insight into treatment between testers both across the marketplace and between individuals.

Our results indicate that the troubling disparities that our testing detected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic continued with implementation of PPP lending. Our findings show that there were statistically significant disparities between the groups of testers using the chi-square difference test across the marketplace. We found:

- A difference in levels of encouragement in applying for a loan.

- A difference in the products offered.

- A difference in the information provided by the bank representative.

In addition, an analysis of matched-pair tests where testers requested loans in Washington, DC, found that in 27 out of 63 (43%) tests that there was a difference in treatment with the White tester receiving more favorable treatment as compared to the Black tester in the small business pre-application arena. Further analysis revealed that Black testers experienced differences in treatment through a difference in the information requested of the tester and in two different tests, Black male testers were offered home equity line of credit (HELOC) products instead of/in conjunction with small business loan products.

In 12 out of 27 (44%) tests where we identified disparate treatment as a part of our fair lending review, lenders not only discouraged the Black testers from applying for a loan, but simultaneously encouraged similarly situated White testers to apply for one or more loan products. This “double impact” on minority applicants, discouragement and failure to provide complete information, not only limits minority access to credit, it also damages the credibility of the small business lending community.

Further, these actions are all fair lending violations of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), which requires that equally qualified borrowers are able to access credit regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender and other protected classes.

To address ECOA’s anti-discrimination provisions in the small business arena, financial institutions need to implement rigorous compliance programs that include matched-pair testing of their bank branches and review of their decision to deny a PPP loan to ensure that there is no disparate treatment or impact. The federal government can aid compliance efforts by ensuring that data related to small business lending is made public. The SBA should immediately release the business name and address for businesses that were able to access a PPP loan for less than $150,000 and the terms of those loans, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) should fast track its efforts to implement the Small Business Data Collection provision of the Dodd-Frank Act, Section 1071, that requires lenders to disclose small business loan data. Without concerted policy action to improve and encourage minority small business ownership, and the availability of capital, existing disparities will continue, hampering economic development in minority communities.

Introduction

Over 10 million people worldwide have tested positive for the coronavirus (COVID-19) since we first became aware of it at the end of 2019, with the United States leading in the number of positive cases. To lower the curve, some state governments have ordered stay-at-home decrees resulting in a recession as all non-essential businesses are closed to the public. To alleviate the economic effects of the pandemic, President Trump signed CARES Act on March 27, 2020.

The PPP is a subsection of the CARES Act to aid small businesses impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. It is a loan program designed and run by the Small Business Administration (SBA). Business owners were only able to apply for this funding through an existing SBA lender like a Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI), bank or credit union. It was not possible for an applicant to apply through the SBA website; in contrast to the way people normally apply for SBA disaster loans.

The PPP provides a direct incentive for businesses to stay open and keep workers on the payroll. The funds received through this program are forgivable if the money is used for payroll, rent, mortgage interest or utilities. However, the majority of the funds must go to payroll. Money through the PPP was initially opened to businesses on April 3, 2020. The first $349 billion was exhausted after just two weeks and Congress went on to approve an additional $310 billion to be added to the PPP fund. This second round of funding began April 27, 2020. It was expected to run out faster than the first round, but as of July 10, 2020, there is still over $100 billion unclaimed. NCRC began matched-pair fair lending testing on the first day of the second round of PPP funding.

The entities eligible to receive PPP funding are broad. The SBA guidelines state that any business that meets the SBA size standard, which is a businesses with less than 500 employees, 501(c)(3) non-profit organizations, 501(c)(19) veterans organizations, sole proprietors, independent contractors and self-employed persons affected by coronavirus were considered to be eligible.

As of July 10, 2020, the amount of funding remaining was $132,189,028,196, despite predictions that the second round of funding would run out quickly. $517,417,286,175

in loans have been made by 5,454 different lenders. Among the 4,907,655 current recipients of the funds, the average loan size is $105,000, with the top lenders being large commercial banks. Of all loans made so far, 86.5% were for an amount less than $150,000. In the District of Columbia, 12,536 loans have been processed for a total of $2,119,096,826 in PPP aid disbursed so far. Industries receiving the highest percentage and net dollar amount of loans include Health Care/Social Assistance, Professional/Scientific/Technical Services and Construction.

PPP Lending to Minority-Owned Businesses

COVID-19 has had a disproportionate negative effect on Black communities. Not only is the death rate for Black people 2.3 times higher than the rate for White people, the number of Black businesses lost between February to April 2020 is almost twice that of the national business loss rate. A reason for this higher percentage is the higher number of Black businesses in sectors that were heavily impacted by COVID-19.

News sources have reported that minority businesses are having trouble accessing funding through the PPP program. There is a lack of data around the number of loans that minorities and women-owned businesses received as demographic information was not initially collected by the SBA. A survey conducted by Color of Change and UnidosUS highlights this lack of access in regards to PPP lending. It found that only 12% of Black and Latinx owned businesses were successful in receiving the full funding amount that they requested and that 41% had not received any assistance.

Not enough attention has been given to the role that systematic discrimination plays in the ability of minority business owners to access capital. We conducted 63 fair lending matched-pair audit tests of financial institutions in Washington, DC, and found a difference of treatment in 27 out of 63 (43%[1]) matched-pair tests with the White tester being favored over the Black tester in the pre-application arena.

Testing Methodology

NCRC, in collaboration with our academic partners, conducted and analyzed 63 male and female race tests (32 White male v Black male and 31 White female v Black female) in the Washington, DC, MSA for a total of 126 interactions between testers and banks. In these tests, we contacted 32 bank branches representing 17 financial institutions. This sample of banks in the Washington, DC, market were randomly selected to represent a broad cross-section of the small business lending market. The banks selected ranged from lenders with assets over $10 billion to community banks. The purpose of the research was to determine the baseline customer service level that male and female testers of different racial backgrounds received when seeking information about small business loans to help keep their businesses open during the COVID-19 crisis. Bridge loans are short term loans that under normal circumstances a business would take out to bridge a financing gap. For example business may take out a bridge loan to pay inventory. The PPP is considered a bridge loan. NCRC started testing on April 27, 2020, the first day of the second round of PPP lending and completed the testing on May 29.

Testing is a critical enforcement tool in the fair lending sphere used to ensure equal access to credit. Federal agencies also conduct testing to investigate when they have been alerted to suspicious behavior. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) partners with fair housing groups to do testing under their Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP). The Department of Justice (DOJ) Civil Rights Division has taken on many cases developed from their testing program. Additionally, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has taken enforcement action against Bancorpsouth after implementing testing that revealed multiple threats to consumers’ fair and equal access to mortgages. The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld testing as a crucial private enforcement tool in fighting against civil rights violations.

NCRC and our academic partners conducted these tests as telephone tests since many bank branches were closed to in-person services because of the pandemic. Tester profiles were controlled with racially identifiable names and each tester was required to pass a voice panel test to determine whether or not their perceived race could be determined over the phone. Testers were only used if their voice was perceived to be racially identifiable above 70%. Research shows that the race of an individual can be often determined by their names alone. We selected profile names after researching names most often perceived with a particular race, and like testers’ voices, we presented those names to a national survey panel to identify names perceived to be highly correlated with gender (male and female) and race (Black and White). Research also reveals that linguistic profiling occurs over the phone, and that many Americans are able to accurately guess social demographics such as race over the phone after a few sentences.

This study, like our previous studies, was designed to answer the following research questions. Are minority and non-minority small business owners with similar economic and business profiles:

- Presented with the same information?

- Required to provide the same information?

- Given the same level of service quality and encouragement?

The matched-pair mystery shoppers had nearly identical business profiles and strong credit histories to inquire about a small business bridge loan to maintain their business during the COVID-19 pandemic. The profiles of all testers were sufficiently strong that, on paper, they would all qualify for a loan. Furthermore, the female and Black male tester profiles were intentionally designed to be slightly better than their White male counterparts in terms of income, assets and credit scores. This was done to make it a more conservative test of any differential treatment.

Immediately following the interaction, testers were asked to answer either yes or no about whether specific behaviors, queries and comments were made by bank small business lending specialists. They were also required to provide a narrative of the interaction.

We applied statistical analysis in evaluating whether differences in the interactions between White testers and Black testers were significant across all the banks visited. This analysis, known as a chi-square test for independence, is a particularly robust way for social scientists to evaluate whether or not there are substantial differences in outcomes between groups. The simple “yes or no” categorization of the interactions between bank personnel and testers and the number of interactions observed ensure a high level of validity. To ensure we were analyzing and comparing cases that reached a similar point-of-contact with the bank, we only included in these analyses those cases where the tester was able to speak to a bank representative regarding their small business loan request. In total, there were 29 White males, 25 Black males, 29 White females, 25 Black female tests analyzed using Chi-square difference tests.

The narratives were individually analyzed independently by two fair lending experts as a matched-pair set to determine a difference in treatment under fair lending standards. The analysis of the narratives included situations where the testers were unable to speak to a loan officer. The testing revealed four fair lending categories of discriminatory interactions: level of encouragement, difference in products offered, difference in information provided and difference in information requested. These differences in treatment between White and Black testers are particularly troubling because the combined effect of these various differential treatments may lead to feelings of discouragement and despondency among minority entrepreneurs in the financial marketplace. There is some evidence that this may already be happening. The Federal Reserve Small Business Credit Survey 2019 Report on Nonemployer Firms states that 13% of all small business owners do not apply for credit because they are discouraged. However, in the same report, the reported rate of discouragement among minority entrepreneurs is markedly higher at 27% for Black entrepreneurs and 21% for Hispanic entrepreneurs.

The ECOA is the fair lending law that has jurisdiction over small business loans. ECOA makes it illegal for a member of a protected class to be discriminated against in any aspect of a credit transaction which includes the pre-application arena. Protected classes under ECOA are: race, color, religion, national origin, sex, marital status or age (provided the applicant has the capacity to contract); to the fact that all or part of the applicant’s income derives from a public assistance program; or to the fact that the applicant has in good faith exercised any right under the Consumer Credit Protection Act. Discrimination occurs when a protected applicant is offered different products, provided different information or experiences differing levels of encouragement to apply compared to the non-protected applicant. Discrimination can be found through either disparate impact or disparate treatment. Disparate impact is a neutral policy that has an adverse disproportionate effect against a protected class. This can be shown through the use of statistical tools. Disparate treatment compares the treatment between two individuals with one of the individuals being a member of a protected class. Disparate treatment can range from subtle differences in treatment to more overt cases. The chi-square analysis reveals the disparate impact seen across the marketplace that requires large scale reform, whereas the fair lending analysis of the individual matched-pair tests reveals additional disparate treatments which can be addressed individually through cases filed under ECOA.

Difference in Treatment

A fair lending analysis of the individual matched-pair tests found 27 out of 63 (43%) tests revealed a difference in treatment in violation of fair lending laws. We observed a difference of treatment experienced by the Black testers through: difference in levels of encouragement, difference in products offered, difference in information provided and difference in information requested.

Of the 17 different financial institutions tested in this audit, 13 institutions had at least one test that showed the control tester was favored. Black females received worse treatment in 59% of the tests that we found a difference of treatment in. Overall, there were 49 different instances of discrimination that the Black testers experienced.

Difference in Level of Encouragement

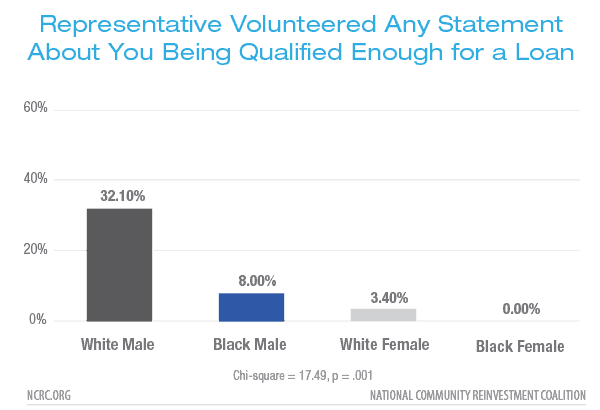

The analyses revealed that White testers were encouraged to apply for loans with the financial institution more often than Black testers. Encouragement to apply for a loan is revealed through statements that are made or not made to different testers. We utilized Chi-squared tests for differences of the means to assess whether the observed inconsistencies in the treatment of the testers were statistically significant across the market. Bank employees informed White testers that they would qualify for a loan at a significantly higher rate than Black testers. When gender is introduced as a test condition, we found that Black males were told that they qualified at a significantly higher rate than White females. A similar trend in gender disparity was observed for Black females, but this was not statistically significant. However, it is worth noting that in this sample of testing, none of the Black female testers were encouraged to apply through qualifying statements.

Some specific examples of this difference in treatment are:

- The Black tester was asked where he banked and said “that I normally bank with XXX and did not have an account with YYY. She apologized but explained that without an account, they wouldn’t be able to assist.” The White Tester was “asked where I currently banked, and explained that I would need to open a business checking account to establish a relationship with YYY before I would be able to apply…She assured me that she would send information on both the PPP loan and small business loan via email, as well as a list of the required documents I would need to submit [to open a business checking account].”

- When the Black tester called, they were told before receiving any information about products they would need to come into the bank in person. “She told me that since I was not a current XXX customer that she would have to physically identify me. She offered to make [an] appointment for me to come through the drive through so she could identify me and view my state issued ID or driver’s license.” The White tester was given specific information about a line of credit and secured loan including interest rates, fees and approval times.

This is a fair lending issue as the Black testers are experiencing a lack of encouragement relative to White testers in becoming customers of these banks. The testing narratives revealed the practices used by the financial institutions, like requesting the tester to be physically identified or not discussing products with them if they are not a current customer, that show a lack of encouragement in applying to minority business owners. This type of differential treatment is a violation of ECOA.

Difference in Products

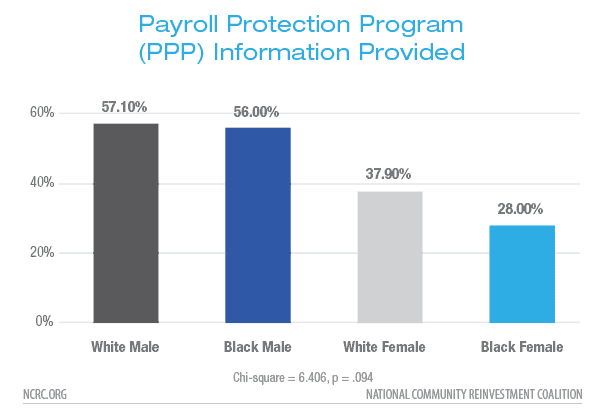

Using the Chi-squared test for statistically significant differences across the market, we found a statistically significant difference by gender. Women as a collective group were offered less information about the PPP products compared to the men as a collective group.

We observed difference in treatment for products offered in the following example:

We observed difference in treatment for products offered in the following example:

- TheBlack tester was told the “only option they were offering was the PPP loan and to go to [the banks website].” The White tester was told “they have a business line of credit up to $100,000…[the bank employee] stated that approval times are a little longer right now because of COVID-19, but they are 2-3 weeks maximum. She went on to state that there are no fees.”

This is a fair lending violation as it is illegal to offer different products to equally qualified individuals. The profiles used in this testing were created so that the Black tester was better qualified than the White tester; however, in this test we observed the White tester receiving information about a small business line of credit through the bank and the Black tester was told only about the PPP.

Furthermore, in two different instances Black males were offered a Home Equity Line of Credit (HELOC) product instead of/in conjunction with small business loan products:

- Black tester was told about a HELOC and no small business products. White tester was told to apply for a PPP loan on their website.

- Black tester was told about PPP loans and HELOC. White tester was told about PPP loans, business loans and a business line of credit.

In these specific tests, it appears that within the first few minutes of the conversation, the bank employee had pre-determined that the Black male will not qualify for a business loan so the employee steered the tester to a non-business product. When in actuality for these tests, the Black tester was more qualified than the White tester for the business loan and should have only been offered a business product.

Difference in Information Provided

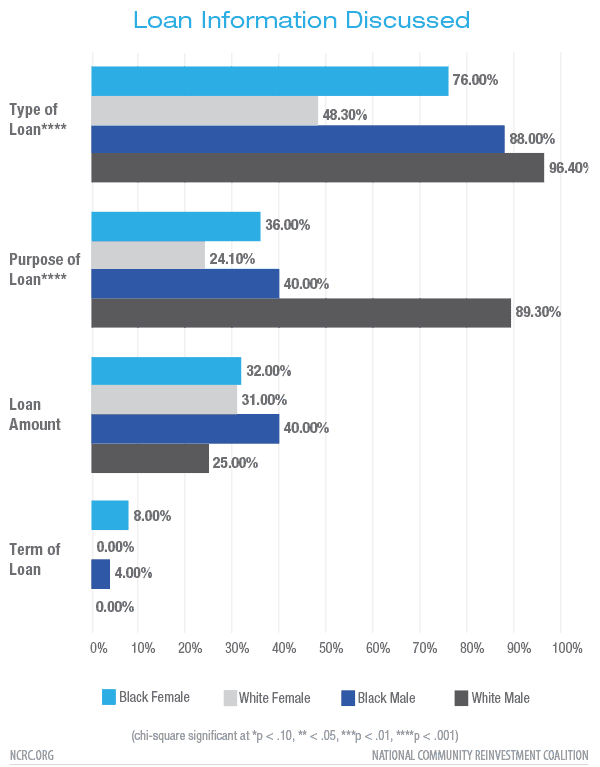

Information gathered in the bank interaction provides the basis for decision making by entrepreneurs. Using the Chi-squared test, there were statistical significant differences in information provided on the basis of race and gender. Specifically, the audit testing revealed that there was a statistically significant difference in information discussed around the type of loan and purpose of the loan with the bank employee discussing this information more with the White male tester compared to the Black male tester and the female testers. We did not find statistically significant levels of differences for two categories of information provided – loan amount and term of the loan.

A specific example of this difference in treatment is:

A specific example of this difference in treatment is:

- Both testers were informed by bank representatives that the financial institution had put a hold on all business products being offered due to the surge of PPP applications. The Black tester did not receive any additional information after being told about the hold in lending. The White tester was given information (interest rates, timeframes, approval times, fees, payment information) about business products for when the bank would return to funding other products and encouraged to call back when funding started again.

It is a fair lending violation to provide different information to equally qualified individuals. Based upon the information received by the testers, the White tester was informed not just about products the bank offers but also specific information about these products like interest rates. The Black tester who is more qualified, was not told about these products nor information regarding these products.

Difference in Information Requested

We observed that there was a difference in information that testers who were asked to provide in order to receive help from a loan officer. In particular, we found:

- Both testers were offered a line of credit, however, the Black tester was asked more personal questions about identifying his business, and told less information such as fees and interest rates. The White tester was told specific information without having to verify any information about his business.

It is illegal to provide the White tester with more comprehensive information than the Black tester about the same product when the Black tester has a better financial profile. The Black tester had to answer questions in order to identify their business as legitimate and eligible for loan products, whereas the White tester was not asked any of these verifying questions before receiving information on products.

Double Impact: Discouragement and Different Products Offered

We have observed a double impact in 12 tests where the White tester was favored. This double impact, revealed as a part of our fair lending review, occurred when the bank employee discouraged a Black tester from becoming a customer of the bank while simultaneously encouraging a similarly situated White tester to become a customer by informing them about different loan products. This double impact on minority applicants, discouragement and failure to provide complete information, not only limits minority access to credit, it also damages the credibility of the small business lending community.

- The Black tester was told by a bank representative “that she is not able to give me any information” and was referred to call a different branch. The White tester was recommended a business line of credit and told about applying for a business credit card with the bank, “that two of the different options would be a credit card or a line of credit. He went on to state that they are offering a credit card with 0% interest for 12 months and told me that he thought it would be a great option.”

- Black tester was encouraged to go back to his bank for PPP and other loan products as the bank could not offer him anything. White tester was told about loan products he could apply for if he became a customer.

We observed this double impact in 12 out of 27 tests where differential treatment was identified which is 19% of all tests and 44% of differential treatment tests. We identified more cases where this action occurred with the Black male testers than the Black female testers.

Recommendations

The testing in the small business pre-application arena under normal circumstances has the ability to reveal fair lending violations. In the pandemic, it is the responsibility of both the financial services industry and government to ensure that capital is accessible to equally qualified applicants. Below are recommendations for both government and industry:

Governmental Recommendations:

Implementation of Section 1071

The CFPB needs to fast track implementation of Section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Act immediately. Delays in the implementation of Section 1071 have already impaired both the federal government and the public’s ability to monitor fair access to credit. Implementation of Section 1071 would have required the PPP loans to collect important demographic information which would have helped allocate resources to minority businesses to better ensure their ability to successfully ride out this recession.

Require the Collection of Demographic Information in Future Disaster Response Small Business Lending Programs

If future disaster response legislation includes small business lending, Congress needs to include a data reporting requirement. This requirement must include borrower demographics, loan amounts and other data that can better assess where these disaster funds were allocated.

Small Business Administration (SBA) Needs to Release Data from PPP Lending

The SBA is withholding the release of specific demographic data such as the business name and address from the public for PPP loans that were less than $150,000. The SBA has reported that as of June 30, 2020, 86.5% of all loans were for less than $150,000. The PPP loan is similar in nature to an SBA 7(a) loan with similar data captured for 7(a) loans including both names and addresses; in addition, the SBA releases data around 7a loans quarterly. This lack of transparency must be addressed in order to determine who exactly this program benefited and to assess whether or not the PPP was successful in aiding small businesses.

Industry Recommendations:

Statistical Analyses of Denied or Not Fully Funded PPP Applications

Financial institutions should invest time into reviewing PPP applications they denied or did not fully fund to ensure there is no difference in treatment or disparate impact created by their decision making.

Compliance Program

Financial institutions need to implement a compliance program to ensure that they are in compliance with ECOA and other fair lending laws. This compliance program must include matched-pair testing as testing exposes weaknesses that need to be corrected through training.

Training

Financial institutions need to train their employees better. Training is a valuable tool that provides employees with an understanding of protocol, expectations and laws.

Implement Call Back Systems

Banks should implement a phone call back system within each branch. 63% of tests required at least one tester to call the bank more than once to speak with someone who could provide information. In some cases, testers were disconnected while waiting to speak with a loan officer due to high call volumes. Once disconnected, the testers had to get back into the queue and start the wait all over again. This type of discouragement was seen across all tests and led to frustration with the financial institution before even speaking to a representative. This negatively affects the way customers view a bank, and implementing a call back system would increase the marketing of products to new and existing clients.

Conclusion

Small businesses are the backbone of the economy and the COVID-19 pandemic hit them the hardest. It is crucial that disaster recovery products such as the PPP are created and made widely available for businesses to remain resilient in the face of economic hardships. However, discrimination plays a significant role in minority and women-owned businesses not being able to access PPP loans. The difference in treatment found in the level of encouragement, products offered, information offered and information requested are proof that there is still work to be done to ensure all equally qualified business owners have equal access to credit.

[1] The frequency rate of one test at a financial institution is not statistically significant, but the overall frequency for all institutions tested is an alarming trend.

Photo credit: Coachwood/stock.adobe.com

Table of Contents

Download the full report (PDF)