Women Owned Small Businesses In the D.C. Metro Region:

Challenges & Resilience During

the COVID-19 Pandemic

July 2021

Image: ©loreanto

— Key Takeaways

- Disparities in the accessibility of capital and federal aid may have impacted minority women-owned small businesses far greater than other businesses due to their historical exclusion from banking and lack of banking relationships.

- More public and private sector spending should be directed toward supporting minority women-owned businesses in order to produce greater family and community wealth.

— Key Findings

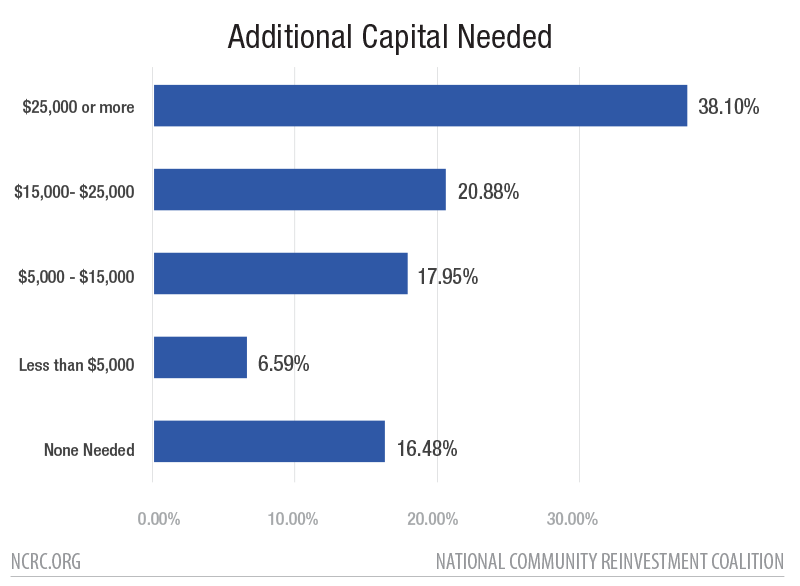

- 77% of 274 surveyed businesses reported that they had unmet funding needs of $5,000 or more.

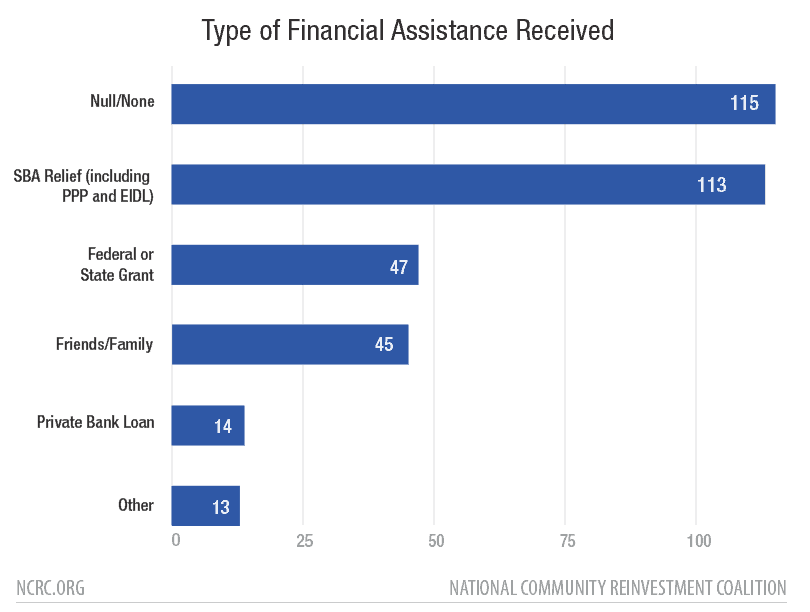

- 41% percent of survey respondents received federal relief from the SBA, yet 42% had not sought any financial assistance from any source.

- Only 16% of the businesses had adequate capital available and did not need further aid or investment.

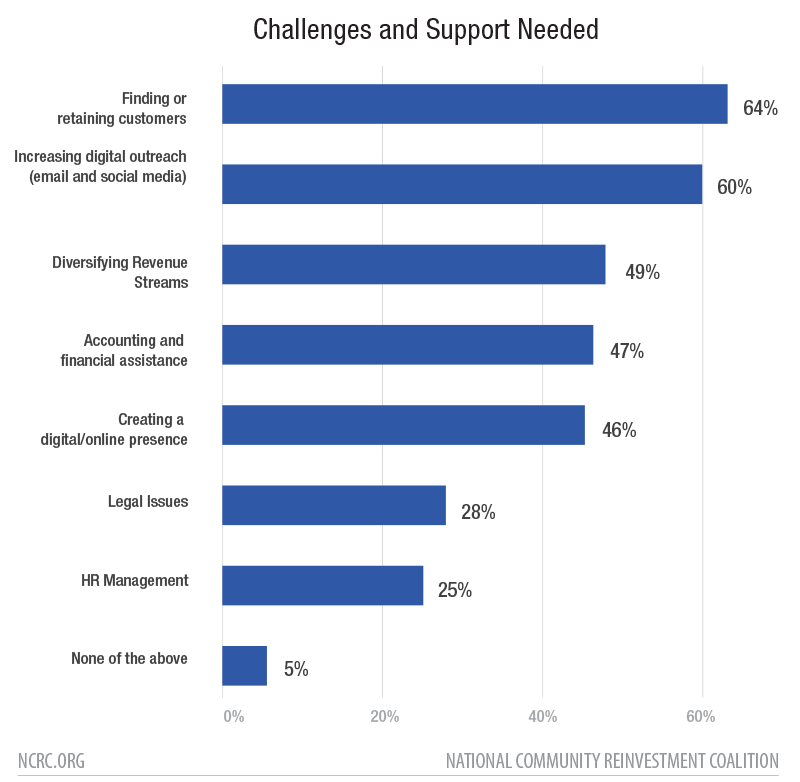

- The respondents who were affected by COVID-19 stated they needed to grow their revenue and sought to do so by accessing affordable capital, diversifying their revenue streams, enhancing their online presence and conducting more digital outreach.

Heidi Sheppard, Project Director, DCWBC

Monti Taylor, Resource Coordinator, DCWBC

Bruce Mitchell, Ph.D., Senior Research Analysis, NCRC

Jason Richardson, Director, Research & Evaluation, NCRC

Executive Summary

Women-owned small businesses in the D.C. region have been hampered by the same barriers that women-owned businesses face nationally: a lack of access to traditional business capital, networks and opportunities.[1] Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the needs of women business owners have drastically changed, and service providers adapted to meet these needs. To fully understand the unique pressures that these owners are facing, NCRC’s DCWBC surveyed 161 of its unique clients and 113 clients from business support providers, offering a window into the experience of small business owners and entrepreneurs in the D.C. metro area. Twenty-six clients of the Latino Economic Development Center were surveyed (five were in Spanish), 29 clients of the D.C. Small Business Development Center, four clients of the DC Fashion Foundation, three clients from the Adams Morgan Business Improvement District, and 50 respondents were business support providers listed in Appendix B. Owners in the survey experienced a variety of impacts from the pandemic. While the pandemic caused some business closures, for others it was an opportunity or just another challenge in their small business journey. Federal relief from the SBA was the most requested financial assistance, but 42% of survey respondents had not sought any financial assistance from federal, state and local grants, or from banks, friends and family during the pandemic. This points out that women-owned businesses are in need of more local financial support and resources to help them grow or relaunch their businesses.

Introduction

The SBA defines small businesses broadly as those with fewer than 500 employees, and startups as those in business for a year or less. Small businesses nationwide faced unprecedented challenges in 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic caused business lockdowns and disrupted core business operations. This challenge required shifts in the marketing and delivery of products and services, with customer-facing businesses being the most impacted. Half of all women-owned businesses are concentrated in customer-facing industries: personal care services, healthcare and social assistance, and professional business services.[2] Women own 90% of all beauty salons, childcare centers (96%) and home healthcare businesses (86%).[3] These businesses make-up 41% of all nonemployer small businesses and 20% of employer firms,[4] still the pandemic has challenged women business owners disproportionately–as women are more likely to be caregivers and have dropped out of the workforce due to loss of work or to care for children and their families.

Historical exclusion from lending and wealth inequalities before the coronavirus outbreak, left minority owned small businesses with no safety net in a more vulnerable position. Female and minority entrepreneurs have had less access to traditional business capital and greater difficulty obtaining the necessary funds to keep their businesses afloat. According to the SBA in 2020, only 16% of small businesses utilized loans from banking institutions to open their small businesses, leaving many small businesses without a credit relationship with their bank, a factor which became crucial when the CARES Act made federally-backed loans that were convertible to grants available under the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). During the rollout of the PPP, banks favored their existing customers when processing the loans, excluding unbanked small businesses from access to the funding.[5] While most small businesses faced severe challenges during the pandemic, there were disparities in the availability of capital and federal aid which may have impacted minority and women-owned small businesses especially hard. The DCWBC survey respondents reported that information on online marketing, introduction to digital business solutions, emergency preparedness and bookkeeping as some of their business needs.

How did the pandemic affect women-owned small business operations in the D.C. area?

This report surveyed DCWBC clients and clients of regional partner organizations on topics such as industry, owner demographics, access to credit and business operations. This information was supplemented with existing literature on the state of women-owned small businesses and existing data sources, such as the U.S. Census’s Small Business Pulse Survey and the Annual Business Survey, 2019.

This study addresses three research questions that shed light on the precarious position of women-owned small businesses in the D.C. area during the current pandemic. The three primary questions examined in this report were;

- What kinds of information, assistance and access, do women entrepreneurs need right now?

- What has been the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the revenue, access to credit, and operations on our clients and other women-owned businesses in the D.C. area and who has been most affected?

- How do women in the survey feel about their business’ outlook before and during the pandemic?

Methodology

This report surveyed 161 DCWBC clients and 113 clients of 22 regional partner organizations, including the Latino Economic Development Center which translated it into Spanish and distributed it to their clients. Questions about the demography of business-owners, start date of the business, the type of business, its revenue and income, financing, and how it had responded to the COVID-19 pandemic were included. The survey of owners and entrepreneurs garnered data about their experiences running a small business before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Following cleaning, deduplication and recoding, there were 274 unique responses.

Once all responses were collated and assessed, descriptive statistics were generated and analyzed. This primary data is compared and contrasted with other studies on women-owned businesses and also with data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Results and Discussion

Quantitative Results

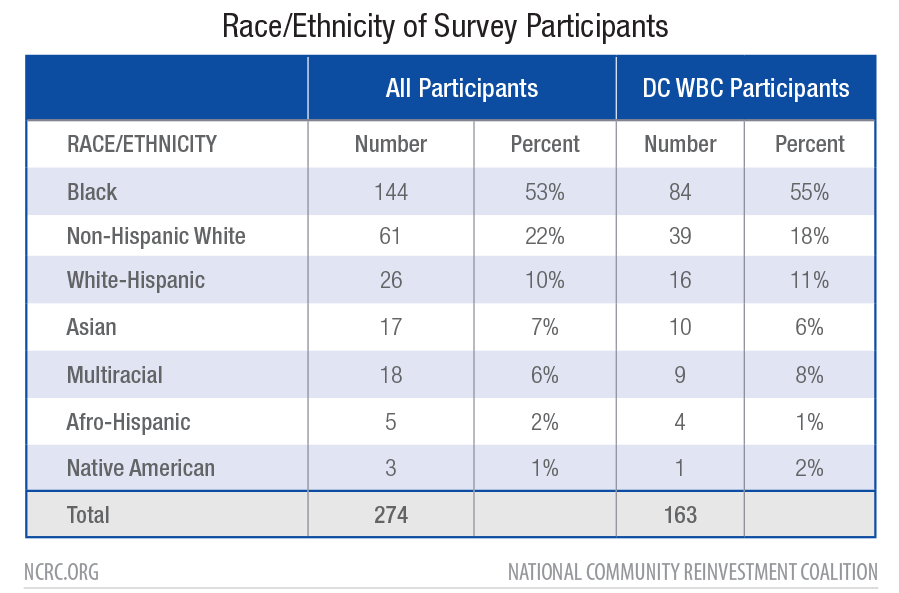

In all, 268 business-owners participated in the study, three of whom identified as male, three as non-binary, and the rest (267) as female. The participants in the survey were a diverse group of women entrepreneurs. The majority of participants were African-American at 53%, with Non-Hispanic White the next largest group at 22%, followed by White Hispanic at 10%, Asian at 7%, Multiracial at 6%, Afro-Hispanic 2%, and Native American 1% (Table 1). The client base of the DCWBC mirrored this demographic, with smaller proportions of Non-Hispanic White and Asian participants (18% and 6%), and higher of Black (55%), White Hispanic (11%), and Multiracial (8%) participants.

Table 1. Demographic composition of all participants in the survey, and of the DCWBC.

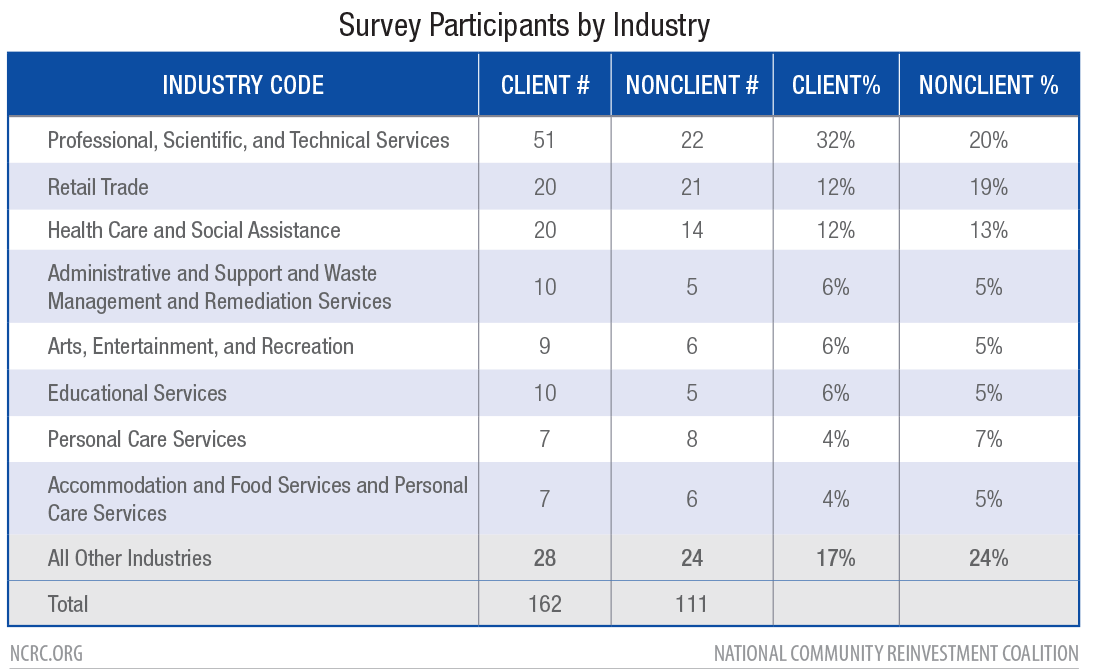

The small businesses included in the survey represented the full range of industries in the U.S., with women business-owners from 20 different types of industries and services participating. Table 2 reflects the primary category of industry in which 5% or more small businesses were engaged. The largest category, representing nearly a third of the businesses, is professional, scientific and technical services, followed by retail trade and healthcare and social assistance – which together constitute over half of the small businesses. Professional, scientific and technical services is a broad category including businesses engaged in legal services, accounting, architecture and design, computer programming, research, and advertising, and the participants reflected this wide variety of endeavors. Next, administrative support, arts and entertainment, educational services, personal care services, and accommodation and food services represent another quarter of the businesses. All in all, services-related businesses constituted almost 64%, while retail trade businesses were almost 21%, with the remainder engaged in manufacturing, construction, finance, information technology, or agriculture. The remainder of the participants (28 clients and 24 non-clients) were distributed across twelve additional industries, none of which had more than four businesses classified under a single code.

Table 2. Type of industries in which survey respondents are engaged. Codes derived from the North American Industrial Classification System. Industry codes for participants totalling at least 5% are included.

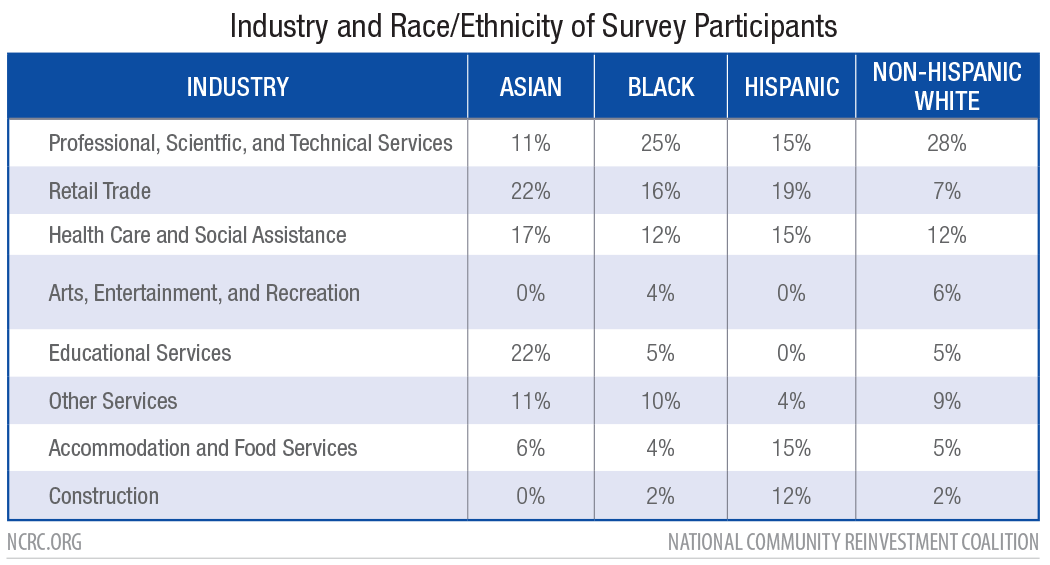

In terms of industry sector by race, the majority of White non-Hispanic and Black survey participants were engaged in professional, scientific and technical services (Table 3). The second most prominent category for Black entrepreneurs was retail trade, then health care and social assistance. For non-Hispanic White entrepreneurs, the second most numerous category is health care and social assistance. Hispanic business-owners were concentrated in retail trade, social assistance, professional services, and accommodation and food services. Asian entrepreneurs were mostly involved in retail trade and educational services.

Table 3. Industry composition as a percent of race/ethnicity of survey participants.

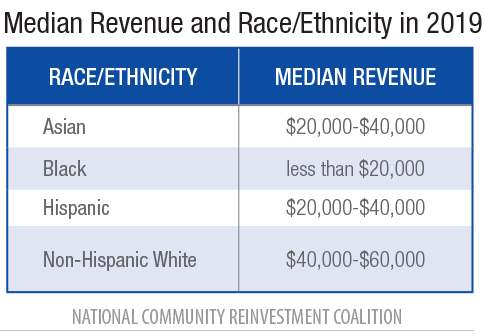

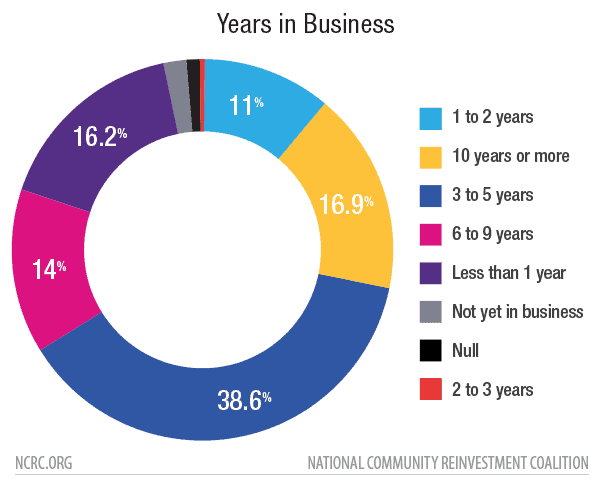

Disparities across racial and ethnic categories were evident in the revenue reported for 2019. Median revenue for Black-owned businesses was lowest—below $20,000 (Table 4), and a large percentage of Black women-owned businesses were also in this revenue category—49%, compared to 30%-33% of Asian, Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women-owned small businesses. The highest median revenue was reported by non-Hispanic White entrepreneurs—between $40,000 and $60,000. Both Hispanic and Asian business-owners reported median revenue levels between $20,000 and $40,000. The disparities between Black and non-Hispanic White businesses are partly explained by differences in the industries that these groups engage in. A higher percentage of non-Hispanic White women (28%) operated businesses in the professional, scientific and technical services than Black woman-owned businesses (25%). The professional, scientific and technical services industry category represents a broad spectrum of business types that vary considerably in revenue. Another explanation is tenure of business operations. Twenty-one percent of the Black woman-owned businesses in the survey had been open less than one year, compared to 15% of those that were non-Hispanic White woman-owned. Additionally, Black women-owned businesses open 10 or more years were 15% of survey respondents, while non-Hispanic White business owners with the same tenure were 21% of the total.

Table 4. Median revenue for 2019 by race/ethnicity of the business-owner.

The participants were asked to specify their current need for capital (Figure 1). Only 16% of the businesses had adequate capital available and did not need further aid or investment. Businesses needing $25,000 or more were the largest group at 38% of respondents. The next were businesses needing $15,000 to $25,000, which was 21% of the survey. Businesses needing $5,000 to $15,000 were 18%, while the businesses needing less than $5,000 were only 7%. Businesses with higher revenue either had high capital needs, or did not need additional capital at all. Sixty-one percent of businesses with revenues over $100,000 needed an infusion of $25,000 or more, while 21% had no need for additional capital.

Figure 1. Capital needs of the survey respondents.

A high percentage, 42% of businesses, received no assistance from federal, state, local grants, from bank loans, or from friends and family during the pandemic (Figure 2). Of the businesses that received support, the SBA’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDl) were the most frequent programs cited, and 41% received this aid. This was followed by a smaller percentage of entrepreneurs receiving assistance from federal or state grants, friends and family and other sources which includes crowdfunding and online lenders.

Figure 2. Assistance received by women-owned businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic as of February 2021. The federal PPP and EIDL programs were still open as of the writing of this report.

In terms of these small businesses needing assistance, over 60% of respondents wanted help finding and retaining customers – and associated with this, 60% wanted assistance expanding their digital outreach via social media or email (Figure 3). A further 45% wanted help establishing an online presence. This indicates that there is a strong need among the businesses for assistance with their digital marketing efforts. After that, diversifying revenue streams and help with accounting and financial assistance were cited as areas of need. This question in the survey was focused on areas in which the DCWBC might directly provide technical assistance to businesses, consequently funding was covered under different topic areas and was not a selection for the participants, which explains why capital acquisition was not a topic in this line of inquiry.

Figure 3. Challenges and assistance needed by businesses.

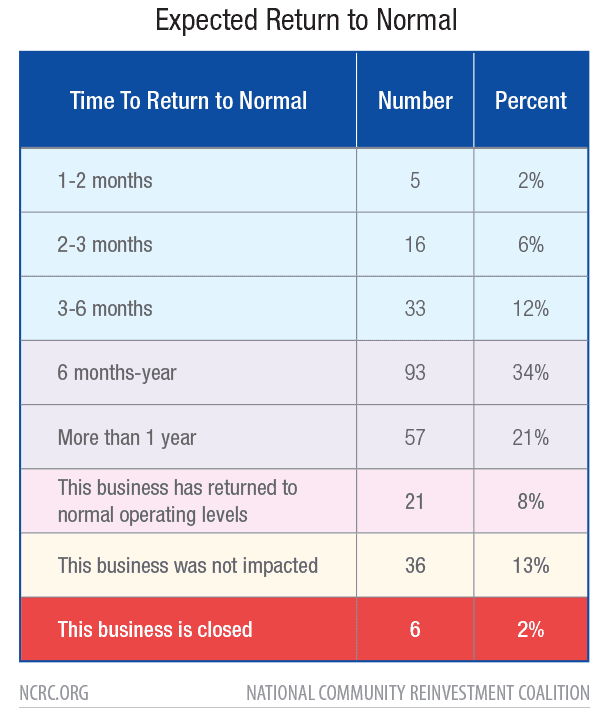

Finally, despite the difficulty operating a small business during the past year, business-owners remained, for the most part, optimistic about the future of their businesses and about the near-term resolution of the pandemic (Figure 4). Seventy-four percent believed that the pandemic will resolve this year, and 20% had already returned to pre-pandemic levels of operation. Thirteen percent were not impacted by the pandemic, of which 40% were in management companies and enterprises, and 29% in retail trade. It is probable that these had an online presence to make up for the difficulty of physical delivery of services. During the past year, social movements to “buy Black,” and others related to the Black Lives Matter movement, have been important drivers of change, and have asserted the importance of supporting the Black business community. All in all, only 2% of the participants in our survey had to close their businesses, though that may not be in line with overall experiences of women entrepreneurs, since the survey may have higher representation of active DCWBC clients who are currently receiving assistance from the center.

Table 5. Survey responses were collected from February 18, 2021, through March 16, 2021. This chart shows the pandemic impact on businesses with expected return to normal business operations expressed by survey participants.

Qualitative Results - DCWBC Survey Of Business Owners

COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic for some participants in the survey was just one of the many challenges they faced in their business journey: “Just another task on this road” and “COVID is just another problem to add to our plates” were common themes in the responses. Business owners discussed pandemic related challenges, adjustments, pre-pandemic state of their business operations and future outlooks.

“I am in the process of establishing my business but the pandemic caused my efforts to be substantially slowed.”

Some women in the survey were optimistic and hopeful for the future: “Hope to get back to it fall 2021,””Hopeful to overcome those challenges in the near future,””This is tough, but it has brought up so many other ways of producing income. I’m excited for the future,” and “Hopefully the end is coming starting in September and going forward.”

While a small percent of owners in the survey had businesses that closed, pivoting or adjusting to the pandemic for most businesses meant temporary closures, creating new programs or services, changing their mission or creating a new business. Some participants’ businesses remained stable or increased due to the demand brought on by the pandemic. These businesses made up a range of industries from food services, healthcare/social assistance and professional business services. One participant, an owner of a certified public accountant firm, wrote,

“There has been an increased need for my services (technical assistance) given the additional government stimulus funding. I have been able to assist fellow minority owned small business owners become more financially savvy by providing one on one financial literacy/ business education to help them use PPP funds effectively.”

Other businesses fared differently. One owner of an engineering consulting firm had to decrease her employees by more than half. Prior to the pandemic she employed 9 people and after the pandemic her employee count dropped to 3. Her tone echoes hope for a return to normal:

“Staying positive; trying to stay healthy and trusting that things will get better and we will be ready when things get better. (A lot of our work involves international travel and our client has suspended all work).”

Two participants not involved in professional business services: a personal chef and a retailer specializing in plant-growing kits both had increased demand. The personal chef pivoted her business to meal delivery services as she mentioned in a follow-up interview,

“COVID forced us to pivot our offering in such a way that we are now more profitable and have an improved customer experience.”

Taking advantage of commercial kitchen space, she was able to navigate the pandemic and grow her business.

The other plant-growing business, despite the increased demand for her product, had to temporarily close her online store due to not being able to expand her home-based business from selling “a few thousand to tens of thousands” of plant-growing kits into affordable real estate space in D.C.

“There is a really strong eco-system for business support in the District but it seems to focus on starting up or established brick and mortar businesses. I fall in the middle…there simply isn’t space or funding for someone like me.”

The greatest challenges to adapt were posed for businesses engaged in personal care services and other “non-essential” industries such as international travel, touring, and some business owners dependent on or engaged in childcare. Business owners dependent on local markets and pop-ups expressed the challenges with decreased patronage. One participant stated the local markets, “were a huge source of income” for her. Some business owners that were considered “non-essential” discussed the difficulties of marketing the needs for services in a state of crisis. These businesses ranged in services from real estate development, professional staging and coaching: “challenging to articulate to the need,” “mental wellness and life coaching during this pandemic has been a challenge.”

Customer acquisition and retention was a challenge for all business owners after heavy social distancing restrictions were lifted due to job losses, as one participant stated, ”people are not working and they do not have money to come to the salons.” Survey respondents with brick and mortar businesses in personal care services (hair salons and spas) owned by Hispanic, White and Asian women were more likely to have their brick and mortar locations opened with restrictions after the pandemic than Black-owned businesses in the same industry (hair salons). Despite these challenges the tone of one participant is unwavering.

“In order to continue working and keep the bills paid, I turned my apartment into a salon by day and living space at night. It’s working now, but it’s time to separate the two and expand business.”

Still some business owners have lost their brick and mortar locations and need assistance in reestablishing their salons.

“It has been insanely challenging. I shifted by focusing on different revenue streams… But, my salon still needs capital to get back on our feet.”

Mothers with the added stressors of school closures and losing child care, expressed the challenges of working full-time in their businesses and simultaneously providing child care and support:

“Much of my business depends on (having) childcare. With children still out of school, this makes it difficult to plan and take on new clients and do my work.”

“…struggled to have the time to push the business to its fullest potential without schools/daycares open.”

Time constraints were also challenges for non-mother business owners, citing struggling to find the time to implement new marketing strategies, while also engaging in core business operations and lengthy applications for pandemic relief. Business owners in childcare and educational services experienced different impacts. Overwhelmly, childcare providers had positive outlooks in supporting their local communities child care needs – serving essential workers and adapting to protocols to remain safe and healthy. One participant stated:

“Just a little disappointed on the entire process on how much small businesses give to the DC area and the support level is not the same.”

One participant, a substitute teacher, discussed her struggles with job loss and health that greatly decreased her household’s income, being able to navigate only through her husband’s ability to work.

Financial Capital and Lending

Capital needs for the business owners were primarily centered on general operating expenses: equipment, marketing and payroll. Equipment needs included a broad range of material supplies and machinery for business operations: inventory, sewing machines, laptops, prototype creation for start-ups, mobile trucks (for food, transport and other personal care services), and Point of Sale technology. Technology needs also included website infrastructure, application and software development. Payroll needs “to hire new employees,” “to cover salaries,” “pay the owner…me” and “paying contractors” were common among the responses. Other funding needs included access to capital to cover rent, obtain rental space, renovations, licensing and to fund current and/or new programs/production.

Forty-two percent of respondents had not sought support of any kind. Challenges with accessing capital was a key theme. Business owners who had not applied for a PPP loan cited a lack of accounting support, financial statements, legal knowledge and lengthy applications as key reasons for not pursuing this relief.

Brick and mortars in D.C. struggled to pay rent, despite policies requiring commercial rental payment plans. With decreased revenue, owners are still struggling with overhead expenses:

“Our landlord has not decreased our rent despite our decrease in sales – nor have other service providers. I understand that they all have bills to pay but it seems unethical to profit off of small businesses right now. I wish there was a policy to address this issue.”

For other owners as mentioned in the previous section, this meant closing their physical location. Home-based businesses also struggled with household rent, juggling work responsibilities within their business, negotiating contracts and creating an online presence while also trying to navigate relief, and for one business owner, “poverty and interdependence.” Two participants noted utilizing pandemic unemployment assistance (PUA) to navigate loss of revenue.

“Thank God for PUA. This has literally kept my EDWOSB (Economically Disadvantaged Women-Owned Small Business) alive.”

The lack of access to capital was the key reason for many owners’ inability to expand their business by hiring new employees, or purchasing technology needs and/or maintaining their website.

“Black women business owners are at a sharp disadvantage when it comes to accessing capital to continue or improve business operations. We need more viable opportunities to succeed in our entrepreneurial endeavors.”

“I am having a very difficult time rounding my business. I really want to find a good location where I can have customers but I don’t have money.”

“I am in need of support to get my business off the ground. I have done a significant amount of work on my own with my own money but now I need assistance to take me to the next level so that I can begin to identify clients/organizations and bring in revenue.”

Due to the inability to find affordable warehousing space in D.C, a woman-owned e-commerce business will have to move her business out of D.C. She feels that home-based businesses have less opportunities to grow. During the last year, her business grew from producing a few thousand to hundreds of thousand orders, but not having access to affordable warehousing space in D.C, she had to outsource space and labor to scale her business. As she noted:

“My business has grown rapidly since the pandemic, which I am really thankful for. But trying to physically scale a business in D.C. is really challenging. I have been looking for nearly a year for a warehouse space I can afford and I haven’t found anything.

In addition to the difficulties of low cash reserves, discouragement from seeking financial products was also an issue:

“The SBA lender match tool showed that I matched with 11 lenders but none actually reached out to me. Going to the lenders directly, I was told over and over (by White male bankers) that I shouldn’t apply for the loan. That I should stay small longer – share a space, work at night in someone else’s space, etc. That I wasn’t ready.”

Respondents that were able to adapt to online ordering or services experienced increased demands and had the ability to remain in business with assistance from the PPP, grants and other COVID-19 related relief. A small number of businesses received state grants, and there were no discussions of Washington, D.C., grant programs being utilized by any of the participants in the long answer responses. Despite applying for and receiving assistance administered by the SBA, a women-owned transportation company had 35 paid employees prior to March 2020 and in February 2021, her employee count dropped to 10. Her business still needs additional capital to cover the cost of equipment payments.

Location and Business Support Providers

Discussions directly mentioning the District, Virginia and Maryland had varying responses. Business owners mentioning D.C. were on two ends of the spectrum. Some owners cited a lack of affordability and resources to support small businesses. One business in the tourism industry expressed their disappointment in the inaccessibility to outdoor spaces as their primary frustration. The majority of comments about D.C. were not pandemic related, but concerned needing capital support, resources and information to clarify business registrations, licensing and insurance requirements for different business types. These issues expanded to challenges with the DC Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs processes, associated registration and licensing fees. The exceptions were four participants, two who are seeking to move their established business to D.C. One said, “I feel very supported by my city,” and another, the owner of a public health firm, said: “my city needs me.” One business owner in real estate discussed gentrification as being the impending factor to her decrease in business, providing affordable homes to minority families:

“(I) witnessed well over 100 businesses…..go out of business over the last 10 years due to gentrification and escalating lease costs and housing prices up to over $1 million dollars which most minorities cannot afford…I have previous clients who come back to me or send their friends and children – Thank God.”

Many owners discussed being “grateful” for support and being able to “stay afloat.” Business support providers and community support was a common theme from respondents, citing that they remained open and saw their businesses as providing supportive services within their community:

“Without the help of the DCWBC, I would still be contemplating my idea.”

“I have been very grateful for the free (training and networking) webinars offered through the DCSBDC and the GWHCC. I also benefited from a consult through the DCSBDC.”

“The community has been quite supportive and expressing gratitude for us remaining open.”

Maryland respondents mentioned the Maryland’s Women’s Business Center and their gratitude for receiving business counseling services, two respondents directly mentioned state of Maryland grant programs.

“Not knowing about funding opportunities like the Maryland Small Business COVID-19 Emergency Relief Loan Grant Fund until the application deadlines passed was frustrating. That said, I am very grateful to have received the two PPP loans and the Prince George’s County COVID-19 Business Relief Fund.”

“Sales and revenues have plummeted to below 1/2 of typical revenues. I have been able to operate and stay open thanks to the PPP, SBA loans and many grants by Maryland Department of Commerce and Montgomery County’s Economic Development departments.”

One respondent directly mentioned a Virginia county grant program.

“We are new business owners after more than 30 years of federal government service. My husband is a veteran and I am a female. We are grateful for the support we’ve received from the Vienna Business Association, SCORE, and the Fairfax County RISE Grant program.”

Conclusion

COVID-19 and the resulting stay-at-home orders caused an immediate decrease in entertainment, travel and other non-emergency services, at the same time an increase in demand for delivery and digitally mediated services changed the circumstances of how businesses operated and in some instances created a path for new business creation and pivots for existing businesses. Understanding the economic and social structure that different women-owned small businesses operate in is critical when determining how businesses were able to adapt and the full implications of how COVID changed their business operations. Minority business owners and especially Black women have less access to capital to maintain their businesses in times of economic downfall and are responding to pre-pandemic challenges that created an unequal playing field when competing for financial relief.

Women-owned small businesses demonstrate resilience despite the barriers that would seem to restrict their success. Access to a network of community, business support providers and other joint initiatives helped, but more funding support is needed. Supporting business growth for women entrepreneurs increases economic growth within their households and for the local economy.

Some businesses that received federal relief were able to maintain their operations, but the economic downturn has left other business owners with more losses. Initiatives to support female beauty salon owners would benefit women now. Most importantly a rate for women business owners should be introduced when exploring pricing for rental or commercial spaces. In addition local co-working space for small businesses in manufacturing and affordable warehousing would help women businesses that may still be unsupported.

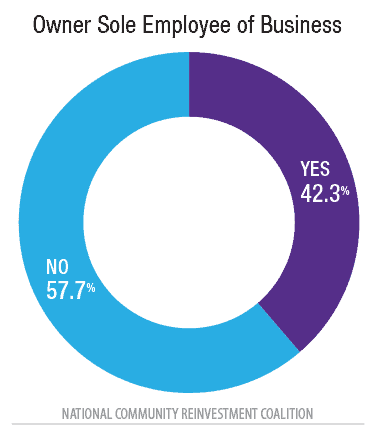

Women business owners need specialized funding for start-ups and for non-employer firms that are not eligible for COVID-19 small business relief programs. In addition, resources to navigate business registration, licensing and insurance requirements for small or home-based businesses in D.C. would help entrepreneurs with the start-up process, an opportunity for the DCWBC Washington, D.C., has the highest business registration cost in the metropolitan region. The Micro-Business Startup Fee Relief Amendment Act of 2017, if passed, would greatly reduce basic licensing fees in D.C. for women owned small businesses with revenues under $100,000. The higher cost of living and renting space in the DMV area may play a role in the ability for women-owned small businesses to grow and scale without capital investment. There are still gaps in support services and investments that women entrepreneurs need. Women business owners benefit from the same policies as women in the workforce, access to affordable child care and paid family leave. Business owners and especially sole proprietors without full-time jobs in the workforce are faced with added stressors in navigating health care and not having paid family or medical leave despite playing a vital role in the local economy, their families and community.

Appendix A

About the businesses surveyed

Appendix B

List of partner organizations:

- Adams Morgan Partnership Business Improvement District

- Coalition for Non Profit Housing and Economic Development (CNHED)

- D.C. Chamber of Commerce

- D.C. Bar Pro Bono

- DC Department of Small and Local Business Development (DSLBD)

- District Bridges

- Georgetown Main Street

- Greater Washington Hispanic Chamber of Commerce (GWHCC)

- DC Small Business Development Center, Howard University (SBDC)

- Washington Area Community Investment Fund

- Washington DC Economic Partnership

- Women’s Business Center of Northern Virginia

- Latino Economic Development Center (English)

- Latino Economic Development Center (Spanish)

- Maryland Women’s Business Center

- DCWBC

- Ringlet

- DC Fashion Foundation

- Ethiopian Community Center

- DC Mayor’s Office on Women’s Policy and Initiatives (MOWPI)

- DC Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs (DCRA)

Appendix C

Literature Review

In January 2021, NCRC’s DCWBC and Research team conducted a literature search on the state of women entrepreneurship.

National Trends; Women-Owned Businesses

Current comprehensive research on women-owned businesses and publicly available data on small business lending to women-owned businesses is sorely lacking. The National Women’s Business Council entered an agreement with the U.S Census Bureau to fund and develop custom tabulations on women-owned non-employer firms from the New Annual Nonemployer Demographics Statistics (NES-D). This, in combination with the Survey of Business Owners, would provide a more comprehensive picture of women-owned businesses in the United States. However, this annual statistical series was last released in December 2020, analyzing data from 2017.[6] Thus, it does not reflect the current status of women-owned businesses. Transparent small business lending data on women-owned small businesses is also unavailable, making it critical for the implementation of Section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act that requires financial institutions to make publicly available loans and lending data on small business owners, including women and minorities. The SBA makes its data on small business lending available, however, research shows that lending from SBA accounts for only 7% of the financial products available for small businesses.[7] Many online financial technology firms, banks and non-profit organizations are publishing reports on their small business lending data but few are comprehensive or frequently updated on lending to women entrepreneurs in the U.S., and thus the unique funding challenges they face are not adequately publicized.

Small businesses owned by women grew significantly between 2014 and 2019, and yet revenues and employment did not proportionally keep up. According to the American Express 2019 State of Women-Owned Businesses Report during that time period the number of women-owned businesses in the U.S. increased by 21%, while the number of all businesses increased by only 9%. As of 2019, women owned more than 42% of all businesses yet generated only 4.3% of total business revenue. More than 1,800 women-owned businesses were being launched daily between 2018-2019. Research from the 2017 American Express State of Women-Owned Business Report showed that since 1997 the share of revenue generated by women-owned businesses has hovered around 4.4% of total business revenue while the share of employment by women-owned businesses has remained close to its 7% share. More than two decades later despite women business ownership growing by more than 2.5 times the national average, in 2019 the share of revenue generated by all women-owned businesses was 4.3% of total business revenue and the share of employment was 8%. Women on average generate only half of the annual business revenue than their male counterparts[8] and minority women business owners face an even greater inequality. The average gross revenue for Black women-owned businesses between 2014 to 2019 was $24,000, compared to $65,800 for all minority women-owned businesses and $218,800 for non-Hispanic White women business owners. If women-owned businesses’ share of total firms (42%) were equal to their share of employment and business revenue, they would make an even greater impact on their local communities and the local economy. According to estimates from the 2019 State of Women-Owned Business Report, if firms owned by minority women were at parity with non-minority women-owned firms, over 4 million new jobs and nearly $100 million in additional revenue would be produced.

For minority women making less yearly income, entrepreneurship is more than just a side hustle, but a pathway to combat racial discrimination and wealth inequity.

Sidepreneurship (part time entrepreneurial endeavors) is a growing means for women to flexibly balance home and job responsibilities, stay in the workforce and maintain financial solvency during a time of extreme challenges. Between 2014 and 2019, growth in the number of women sidepreneurs was nearly double overall growth in women entrepreneurs: 39% compared to 21% respectively.[9] Black and other minority women are more likely to start their business on a part-time basis. Part-time entrepreneurship for minority women increased by 65% between 2014 and 2019, for Black women it increased by 99%. Growth in part-time entrepreneurship for all women business owners increased by only 39%. For minority women making less yearly income, entrepreneurship is more than just a side hustle, but a pathway to combat racial discrimination and wealth inequity. Historical exclusion in banking, lending and lower wealth averages and income contributes to the racial wealth gap found in business revenue for Black women when compared to other racial groups. Research from the Survey of Consumer Finances showed that for households with lower wealth distributions their average business equity was only $20,000, but represented 60% of those households total net worth.[10]

“Nonemployer” businesses, meaning small businesses with no employees other than the owner, describe 90% of women-owned businesses. According to the Consumer Federal Protection Bureau,[11] 9% of both minority and women-owned businesses employ between 1 to 49 employees and less than 0.25% of both have more than 50 employees. According to analysis from the National Women’s Business Council, in 2017 nearly 50% of non-employer firms generated less than $10,000 in annual receipts, but research suggests that even small amounts of business revenue can contribute largely to total household income for part-time business owners. Non-employer women-owned businesses play a significant role in their households and local economies by providing jobs for their owners, according to the 2019 Small Business Credit Survey.[12] Sixty-three percent of non-employer firms stated that their business income was their primary source of income.

The enactment of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES) in response to the economic downfall of the COVID-19 pandemic, provided critical support for Women’s Business Centers and debt relief and direct funding for small business owners. This included the Paycheck Protection Program and targeted small business grants. Lending from SBA’s traditional programs, such as the 7A and 504, to women business owners decreased by more than half in 2020, likely as a result of more women business owners seeking debt free small business relief, with more than $3 billion going to women-owned small businesses in SBA’s fiscal year for 2020 (October 1, 2019 – September 30, 2020, some of these months are during the pandemic), compared to more than $8 billion in guaranteed loans from SBA’s loan portfolio to women in 2019 and 2018.[13] The Paycheck Protection Program was initially designed as a forgivable loan if used primarily to keep employees on payroll, putting women-owned non-employer and smaller businesses at a disadvantage to receive large amounts of this forgivable loan to maintain or pivot their business. As our analysis finds, some small businesses with employees decreased their staff temporarily or permanently to mitigate potential financial risks due to loss of work or to ensure their own health and safety. During the initial rollout of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), banks privately prioritized PPP lending to their existing and larger customers, excluding the most vulnerable entrepreneurs who did not already have an existing relationship with a bank.[14] In addition, mystery shop tests from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition showed that women and minorities were discouraged at a higher rate when seeking information about applying to loans than their non-Hispanic White counterparts.[15] Compounding these challenges, women entrepreneurs who initially sought PPP from community development financial institutions or online lenders were hit with roadblocks as community development institutions and financial technology firms were initially blocked from PPP lending. Community development financial institutions are solely dedicated to providing affordable lending to low-income communities who are traditionally left out of mainstream lending programs.

Income and pay inequality has an impact on business formation and on the ability for entrepreneurs to launch or expand their businesses without investment. Research from the ProjectDiane Founders Survey[16] analyzing data from more than 600 Black and Hispanic women business owners across 36 states and the District of Columbia, found that more than 86% of respondents used capital from their personal savings or income to start their businesses. Women without expendable capital, those who spend the majority of their income on basic needs, are less able to start or expand their businesses. According to MetLife’s 17th Annual U.S Employee Benefit Trend Survey, women were found to be less likely than men to have a savings cushion (49% women vs. 63% men) and are more likely than men to live paycheck to paycheck, 55% of women in the survey stated that they lived paycheck to paycheck compared to 44% of men. Only 24% of participants in the ProjectDiane survey had received outside funding, while 60% noted that acquiring outside investment is a current goal for their business growth.

The report, Gender, Age and Small Business Financial Outcomes, used a subsample from more than 100,000 businesses owned by either one woman or one man with a deposit account in JPMorgan Chase Bank. Their analysis showed that women-owned firms showed a remarkable ability to survive, as on average they started firms with 34% less revenue and had lower revenue growth than men in their first years in business, yet they survived at the same rate as the male owned firms. Other differences between male and female firms are illustrated by the fact that 82% of male business owners had financed their business growth through outside sources while only 18% of women had done so and in this sample, 29% of women-owned small businesses had organic growth. These women did not grow through external debt, as their male counterparts had done, but through profit from earned revenue. It also showed that there is a gender-pay gap in business revenue across most industries in the sample, most pronounced in the services industry which is typically dominated by women.[17] In the health care and personal services industries, men had 58% and 35% higher median revenues in their first year of business compared to women business owners. Despite the unique challenges that women face when starting and growing their business, they are just as likely to survive as a male owned business.

Trends for Woman-Owned Small Businesses in the DC Metro Region

According to the report, Building Inclusive Ecosystems with Intentionally,[18] Deloris Wilson of Georgetown University, analyzed women-owned businesses in D.C. and found that business ownership for women experienced a growth rate of more than 50%. The greatest growth for women-owned businesses was for African American women. African American women in D.C. own slightly more businesses than their non-Hispanic White counterparts but as Wilson points out, the differences in total receipts is daunting. “With about 11,000 firms, White-women-owned businesses earn nearly $3 billion in receipts, while the approximately 12,000 Black-women-owned businesses earn $600 million in receipts.” Businesses owned by Black women generate $54,545 in revenue per business, while non-Hispanic White women generate $250,000 in revenue per business. Hispanic, Asian American and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander women have a smaller percentage of business ownership, (approximately 1,600, 2,000 and 30 businesses respectively) corresponding to their smaller percentage of the total population in D.C. A key challenge in understanding the state of women entrepreneurs is also illustrated in the report, Building Inclusive Ecosystems with Intentionally, by the inability to accurately count the number of women-owned businesses. It is clear that women business owners are underfunded compared to their male counterparts.

The DMV region’s large network of business support providers include accelerators, technical assistance providers, incubators and other co-working spaces. Together, they provide resources, training and investments to small businesses. Deloris Wilson of Georgetown University suggests that continued intentional coordination among the local government and business support providers engaged in investment, mentorship and technical assistance is needed to address the needs of underserved women-owned businesses. Many such initiatives have continued to take place in light of COVID-19, like the Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development (CNHED) in partnership with DC Fashion Foundation and Clyopatra Foundation[19] provided jobs for fashion entrepreneurs to fill the gap in cloth masks being distributed to vulnerable communities. This coordinated effort is one example of many that aim to meet the needs of unique women business owners in addition to entrepreneur-led programming and collaborations with business support providers to dispatch resources and relevant business development training.

New businesses in D.C. continue to face many challenges related to the high cost of commercial office and leasing space in addition to high regulatory fees for business licenses and permits and the increase in commercial property taxes. State and federal government contracting assistance programs like the Women-Owned Federal Contracting Assistance program, 8(a) development program and Certified Business Enterprise (CBE) play an important role in providing access to women and minority owned small businesses to sell their products and services. Coworking spaces like HeraHub and commercial kitchens are also vital for small businesses; they provide access to affordable real estate, kitchen equipment and storage.

The Certified Business Enterprise (CBE) in D.C. supports women further by offering preference in procurement opportunities offered by the District of Columbia and helps position small businesses to better compete in DC government contracting opportunities.

Nationwide and Local Impacts of COVID-19 on Women-Owned Businesses

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women-owned businesses has been significant. Thirty-six percent of small business owners who responded to the Business Owners of Color and COVID-19 Survey[20] reported to be operating with modifications, and 9% were permanently or temporarily closed. Two out of five small businesses experienced revenue decreases between 25% and 75%. Forty-four percent of participants with employees had to permanently decrease their workforce to mitigate lost revenues, and all business owners in the survey are prioritizing grant support for critical COVID-19 relief. Federal relief administered by SBA was the largest relief package to date for small businesses and was requested and received by 41% of business owners in the DC WBC survey. Of those who did not apply for federal relief, 52% did not think they were eligible.

The American Opportunity Enterprise’s COVID-19 Small Business Impact Survey[21] included 1,199 business owners, 430 of which were women-owned small businesses. Slightly more than 88% of these women stated that their business was their primary source of income. Eighty percent reported that despite having high business revenues (14% had an annual business revenue of over 1 million before COVID and 55% made between $50,001 to 1 million), their biggest challenge was cash flow. To mitigate loss revenue due to this decreased cash flow, women owners cut non-essential expenses (50%) and reduced available working hours (33%). 25% of women business owners had no savings to cover expenses and 22% had just enough cash flow to last 1 to 2 months. SBA relief was the most requested financial assistance (60%), and despite the negative effects on their business from COVID, 30% of women-owned businesses had not yet sought financial assistance.

Despite the challenges of the pandemic, access to capital and business closures for the nations’ most vulnerable, creativity and entrepreneurship is up in the United States and District of Columbia. Many entrepreneurs, particularly women who are looking to earn a necessary household income, are taking advantage and starting new businesses. From January 2019 through March 2019, there were 2,991 new business applications in the District of Columbia, by quarter 3 of 2020 (approximately 3 months after the nationwide lockdowns) business applications rose by over 55% (5,287 new business applications in 2020 Q3).[22] During this same quarter, business applications in Maryland rose by 48% and in Virginia by 37%. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, women of color represented the highest growth (89%) for new businesses formed by women daily. These younger and smaller businesses may need more support since the majority of COVID-19 small business relief funding was for businesses that started prior to March 2020.

Appendix D

Survey Instrument (English)

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1xZ4rDNKYuQwj_TAUZHTwkQts0HddtleNo3KgqQnk0Tg/edit

Survey Instrument (Spanish)

https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1uX6PEXVkzyYFKoWi-ww3kXSTfawaZJT-LUY06bE6-Pg/edit

References

- https://www.sba.gov

- American Express 2019 State of Women-Owned Business Report. https://s1.q4cdn.com/692158879/files/doc_library/file/2019-state-of-women-owned-businesses-report.pdf

- American Express. 2017 State of Women-Owned Business Report

- National Women’s Business Council. 2020 Annual Report. https://cdn.www.nwbc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/21113833/2020-NWBC-Annual-Report.html

- Underserved and Unprotected https://coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/PPP%20Report%20Final%20%283%29.pdf

- The State of Black and Latinx Women Founders. digitalundivided . ProjectDiane Retrieved from: https://www.projectdiane.com/

- Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Key Dimensions of the Small Business Lending Landscape at 19 (May 2017) https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201705_cfpb_Key-Dimensions-Small-Business-Lending-Landscape.pdf

- Perspectives on Inequality and Opportunity from the Survey of Consumer Finances (October 2014) https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20141017a.pdf

- https://www.biz2credit.com/research-reports/women-owned-business-study-2020

- Report on Non-Employer Firms. Small Business Credit Survey (2019). https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/fedsmallbusiness/files/2019/sbcs-nonemployer-firms-report-19.pdf

- Lending Discrimination within the Paycheck Protection Program https://ncrc.org/lending-discrimination-within-the-paycheck-protection-program/

- Small Business Administration. Agency Financial Report. https://www.sba.gov/document/report-agency-financial-report

- Gender, Age and Small Business Financial Outcomes. JPMorgan Chase & Co Institute. (February 2019) https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/institute/pdf/institute-report-small-business-financial-outcomes.pdf

- National Business Association. 2018 Mid-Year Economic Report.https://nsba.biz/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Mid-Year-Economic-Report-2018.pdf

- Key Dimensions of the Small Business Landscape. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (May 2017) https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201705_cfpb_Key-Dimensions-Small-Business-Lending-Landscape.pdf

- https://www.self.inc/blog/cities-with-most-female-business-owners

- Building Inclusive Ecosystems with Intentionality. Beacon: The D.C Women’s Founder Initiative. Deloris Wilson. https://georgetown.app.box.com/s/2q4cizm9bvgc8j13d2ioqp4h9rb1iy82

- https://cnhed.org/protect-with-purpose/

- Reimage Wallstreet: Business Owners of Color and COVID-19 Survey. Public Private Strategies (December 2020). https://www.publicprivatestrategies.com/Business-Owners-of-Color-Covid-19-Survey

- Association for Enterprise Opportunity COVID-19 Small Business Impact Survey. https://aeoworks.org/covid-19-survey/

- Financial Wellness Programs Foster a Thriving Workforce. https://www.metlife.com/content/dam/metlifecom/us/ebts/pdf/MetLife_Financial_Wellness_Programs_Foster_a_Thriving_Workforce.pdf

- United States Census Bureau. Business Formation Statistics. https://www.census.gov/econ/bfs/data.html

[1] https://www.sba.gov/business-guide/grow-your-business/women-owned-businesses#:~:text=Office%20of%20Women’s%20Business%20Ownership%20(OWBO),-The%20Office%20of&text=The%20OWBO%20oversees%20Women’s%20Business,obstacles%20in%20the%20business%20world.

[2] https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/legacy/files/downloads_and_links/minority_women_entrepreneurs_building_skills_barr_final.pdf

[3] https://s1.q4cdn.com/692158879/files/doc_library/file/2019-state-of-women-owned-businesses-report.pdf

[4] National Women’s Business Council. Annual Report. 2020. https://cdn.www.nwbc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/21113833/2020-NWBC-Annual-Report.html

[5] https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/05122043/Small-Business-FAQ-2020.pdf

[6] https://coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/PPP%20Report%20Final%20%283%29.pdf

[7] https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/nonemployer-businesses.html

[8] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Key Dimensions of the Small Business Lending Landscape at 19 (May 2017) https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201705_cfpb_Key-Dimensions-Small-Business-Lending-Landscape.pdf

[9] https://www.biz2credit.com/research-reports/women-owned-business-study-2020

[10] https://s1.q4cdn.com/692158879/files/doc_library/file/2019-state-of-women-owned-businesses-report.pdf

[11] Janet Yellen. 2014. Survey of Consumer Finances Retrieved from: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20141017a.pdf

[12] https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201705_cfpb_Key-Dimensions-Small-Business-Lending-Landscape.pdf

[13] https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/medialibrary/fedsmallbusiness/files/2019/sbcs-nonemployer-firms-report-19.pdf

[14] https://www.sba.gov/document/report-agency-financial-report

[15] Underserved and Unprotected. How the Trump Administration Neglected the Neediest Small Businesses in the PPP. https://coronavirus.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/PPP%20Report%20Final%20%283%29.pdf

[16] https://ncrc.org/lending-discrimination-within-the-paycheck-protection-program/

[17] https://www.projectdiane.com/

[18] Gender, Age and Small Business Financial Outcomes. JPMorgan Chase & Co Institute. February 2019. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/content/dam/jpmc/jpmorgan-chase-and-co/institute/pdf/institute-report-small-business-financial-outcomes.pdf

[19] Building Inclusive Ecosystems with Intentionality. Beacon: The D.C Women’s Founder Initiative. Deloris Wilson. https://georgetown.app.box.com/s/2q4cizm9bvgc8j13d2ioqp4h9rb1iy82

[20] https://cnhed.org/protect-with-purpose/

[21] Business Owners of Color COVID-19 Survey. Public Private Strategies. https://www.publicprivatestrategies.com/Business-Owners-of-Color-Covid-19-Survey

[22] https://aeoworks.org/covid-19-survey/

[23]United States Census Bureau. Business Formation Statistics. https://www.census.gov/econ/bfs/data.html