October 16, 2020

To Whom it May Concern:

The National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) appreciates the opportunity to comment on the Department of Justice’s (DOJ’s) merger review analysis. NCRC is an association of community-based organizations whose mission is to increase access to credit and capital in traditionally underserved communities. Our members are actively involved in bank mergers, striving to ensure that mergers do not result in decreases in lending and bank service in their communities but instead provide public benefits in terms of improved Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and fair lending performance. The undersigned 46 organizations support the views of this letter.

In this letter:

- NCRC recommends strengthening the anti-competitive review of merging institutions and increasing public benefits commitments when certain thresholds are reached.

- NCRC recommends including non-banks as part of anti-trust analysis, which, given the rapid unbundling of products, may involve separate analysis for deposits, payments, mortgages, small business loans, consumer lending and perhaps other products.

- NCRC provides examples on how public benefits commitments should be structured to fulfill the statutory requirements.

NCRC and our member organizations have worked to ensure public benefits arising from mergers by negotiating Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs) with merging banks. CBAs commit banks to a specified level of loans, investments and services in the future, which are at a higher level than the previous performance of the merging banks. Robust merger review processes that consider the banks’ future abilities to meet community needs in a non-discriminatory manner best facilitate CBAs, which are a concrete demonstration of public benefit.

NCRC and our member organizations believe that the current emphasis in DOJs merger review guidelines on anti-trust analysis is vital for preserving robust bank competition and affordable bank rates and fees among in all communities. At the same time, however, the almost sole emphasis on anti-trust considerations in the existing DOJ merger review analysis is insufficient in attaining the objectives of public benefits required by banking law.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Act and the Bank Merger Act requires federal agencies to consider the convenience and needs of the communities to be served as a paramount criterion of merger review in addition to anti-trust and safety and soundness considerations. The principle of “convenience and needs” refers to whether banks after mergers will be responding to needs of communities for loans, investments and services. It is not enough for banks to be under the spur of competition and offering reasonable rates if they have significantly reduced branches and loans after their mergers. Banking law recognizes that this would not be an acceptable outcome and requires the agencies to ensure that convenience and needs will continue to be served after bank mergers.

NCRC believes that the both the anti-trust and convenience and needs factors in merger reviews need to be strengthened in order to adjust to the changes in banking over the last couple of decades. The banking landscape has become more varied and technological since the DOJ last reviewed merger guidelines in 1995. Since the internet was in its infancy in the 1990s when the DOJ last changed its guidelines, email and smart phones were not widely available and did not play the role they do today in accessing banking services and receiving statements and disclosures. Banking was far more likely to be conducted in person, in a branch and via in-person interactions between customers and bank personnel.

With the advent of the smartphone and the internet, the banking industry is undergoing profound change with more transactions occurring via mobile banking. Yet, the most complicated transactions such as account opening or an application for a loan will often involve in-person or phone conversations, particularly for low- and moderate-income people. On the one hand, the entrance of digital non-bank financial providers has potentially made the industry more competitive for some products.

On the other hand, these same institutions include large financial providers, such as online mortgage lenders, or online peer-to-peer payment providers with considerable market share. That means that markets in some instances are more concentrated, not less, after the entrance of the online financial providers. In addition, the digital financial providers may not have much of an impact in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods since customers unfamiliar with banking are less likely to engage in significant digital banking transactions.[1] Updating the rigor of both anti-trust and public benefit analyses is imperative in order to ensure that the changes in the banking landscape benefit all segments of the public and do not merely increase consolidation and make banking more convenient for affluent customers.

An additional consideration is that increasing consolidation poses safety and soundness risks as pointed out in the comment letter submitted by Professor Jeremy Kress.[2] The failure of one $250 billion institution is much more threatening to overall economic wellbeing than the failures of five $50 billion institutions. In addition, the largest financial institutions gain unfair competitive advantages such as the ability to negotiate lower rates when they need capital from investors. The DOJ and the banking agencies need to consider heightened safety and soundness screens of mergers resulting in institutions with $250 billion or more as well as ordering anti-trust remedies in approval orders.[3]

The major recommendations of this letter include:

- The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) screen of 200/1,800 should not only include heightened anti-trust reviews but also conditional merger approvals requiring concrete public benefits in the specific geographical areas (metro areas or rural counties) where the HHI exceeds this threshold. Currently, the DOJ and the bank agencies give these mergers heightened reviews, occasionally order branch divestitures and rarely institute public benefits remedies.

- The informal HHI screen of 100 must be formalized to a presumption that DOJ and banking agencies will require public benefits in impacted areas, particularly in underserved counties.

- When a merger results in an institution of a certain asset size of either $10 billion or $50 billion, a public benefit plan for the banks’ entire geographical footprint must be a part of the merger application subject to public comment. NCRC’s preferred threshold would be $10 billion since these are large banks and only about 139 banks in the United States are $10 billion or more in assets. However, if the agencies wanted to focus on the very largest banks for this requirement, the threshold of $50 billion could be used.

- NCRC recommends that the agencies consider designating counties as underserved. This would be defined as counties with low levels of retail lending per capita. These counties would receive elevated attention in HHI and public benefits analyses.

- HHI analysis must not only consider deposits but also separately consider home and small business lending.In addition, the agencies should consider consumer lending and payments but new data reporting requirements would be needed for HHI analysis of these products.

- Public benefit requirements could include CBAs and specific improvements in CRA and fair lending performance measures. Needs to be addressed include those in communities of color, environmental remediation and recovery from COVID.

- HHI analysis must include non-traditional banks and non-banks, many of which are large institutions. Their omission makes markets appear to be less concentrated than they actually are.

Increase in Consolidation Suggests More Rigor Needed in Merger Reviews

While some commentators laud the entrance of the relatively new non-banks into the industry as a competitive force, these commentators gloss over the significant consolidation in the industry over the last couple of decades. The banking industry has national behemoths offering banking services from coast to coast, a phenomenon unheard of in the 1990s when the last updates to the DOJ merger review guidelines occurred. The top four banks in terms of asset size each now have more than $1 trillion in assets with two of them close to $2 trillion in assets. The industry had 24,000 banks in 1966, approximately 15,000 banks in the early 1990s and about 6,000 banks today.[4] The top four banks have about 40% of the industry’s assets today, up from 11% of assets they held in 1990.[5]

Market forces and technology have helped promote this consolidation in contrast to suggestions that technology generally decreases concentration and fosters competition. With the rise of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s secondary market activity in the 1990s, mortgage products became more standardized, enabling large lenders to achieve economies of scale and dominate market positions through automated underwriting and other efficiencies. Non-bank mortgage companies and digital lenders have been able to achieve considerable scale by offering ease and convenience, Federal Home Administration (FHA) and other standardized mortgages.

In 2019, three mortgage companies were among the top five home lenders in the United States, issuing a combined 1.1 million loans.[6] These lenders have large-scale digital operations as well as utilizing brokers and correspondents. The vast market share of these non-banks, attained in a short time period, is a dramatic example of how non-bank and on-line lenders are not necessarily a force for increasing competition in the market but instead may result in markets becoming more concentrated when combining the large market shares of the large banks with those of the digital mortgage lenders.

The consolidation among banks, spurred in part by standardization in the mortgage market, also has adverse impacts in the small business lending market. As banks become larger, they tend to decrease the portion of their loan portfolio that is devoted to small business lending. Small business lending involves underwriting that is less automated than mortgage lending since lenders use a variety of techniques to judge the creditworthiness of small business borrowers and the viability of their business plans. The underwriting for business lending is less conducive to a few key variables and formulas such as, credit history, downpayment, debt-to-income ratios or loan-to-value ratios that mortgage lenders use. Instead, small business lenders often rely on their personal knowledge of small business borrowers to judge their ability to repay their loans. This approach of “relationship lending” tends to be employed by smaller, community-based banks who develop deep knowledge of their customers. When large banks acquire smaller banks, this high-touch personal approach to small business lending often disappears and small business lending declines in a community.[7]

The Institute for Local Self Reliance found that the number of smaller community banks has decreased one-third over the last 15 years and their share of bank assets has decreased by half. As a result, bank small business lending has declined. Small and mid-sized banks controlled just 21 percent of bank assets, but accounted for 54 percent of all the loans provided to small businesses. The top four banks, in contrast, controlled 43 percent of all banking assets, but provided just 16 percent of small business loans.[8]

Financial technology companies (fintechs) might be compensating for some of the loss of bank lending. Federal Reserve surveys find that about 20% of applications of small business loans are being received by fintechs but that applicants tend to be less satisfied with fintech loan terms and conditions.[9] The impact of fintechs are hard to measure due to the lack of data on their small business lending activity and their market shares.

Consistent with the Institute for Local Self Reliance, NCRC research for the Appalachian Regional Commission revealed that when concentration levels on a county level increased, small business lending decreased. NCRC’s econometric analysis controlled for small business characteristics, county income levels, and economic growth.[10] Immergluck and Smith also found that small business lending in low- and moderate-income (LMI) census tracts decreased in the wake of mergers.[11]

It is more than likely that in a number of markets consolidation has made banks more profitable by increasing their economies of scale while at the same time decreasing access to credit, particularly for small businesses. Consolidation may have also decreased lending for LMI customers whose home mortgage or consumer loan needs may involve products that are more specialized instead of standardized products that can be readily sold to secondary market investors. The research on the impacts of mergers on mortgage lending or consumer lending is less extensive than the research on the impacts on small business lending but some studies suggest that a decline of relationship banking and branching has decreased mortgage and consumer lending in LMI communities.[12]

Need for Elevating Public Benefit Analysis in Merger Reviews

The traditional anti-trust analysis must be supplemented by public benefit analysis in order to ensure that communities will not experience declines in access to credit after mergers. The DOJ merger review now focuses on anti-trust analysis. Named after two economists, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) index is the predominant measure of the level of concentration in a market. The HHI is the summation of the squares of market shares of lending institutions. The most common application of the HHI is estimating the level of market concentration of banks using bank deposits. Each bank’s market share of deposits is squared to derive an HHI for a geographical area.

Using the HHI, the agencies currently consider the level of market concentration to be:[13]

Currently, the agencies will subject a merger to a heightened level of anti-trust review if the HHI increases 200 points and the post-merger HHI for the market is around 1,800. In addition, mergers that result in an increase of the HHI of 100 in moderately concentrated markets can warrant additional scrutiny.

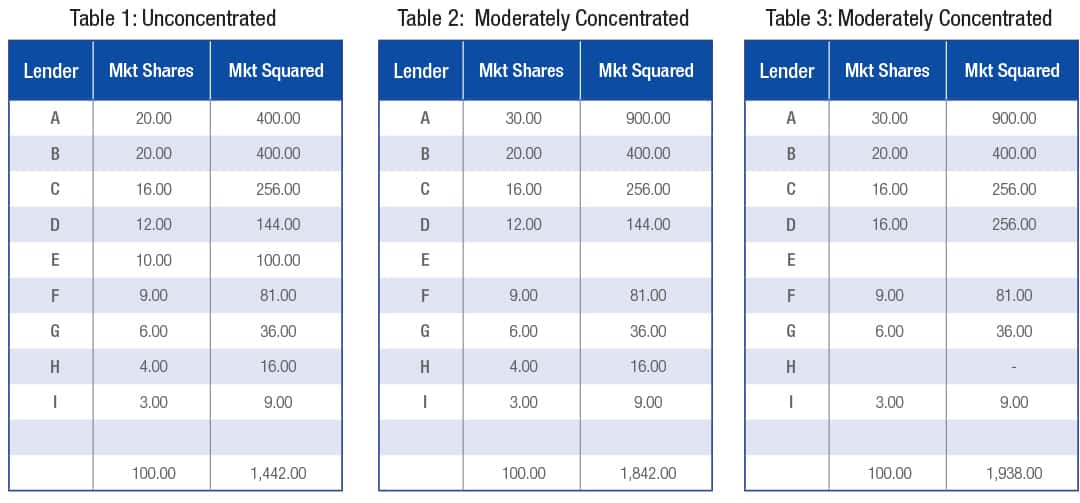

Tables 1 through 3 below illustrate the differences between an unconcentrated and a moderately concentrated market. An overall point is that the HHI formula magnifies the impact of large institutions with substantial market shares. Note that lender H in Table 1 with a market share of 4% only contributes a total of 16 points in the HHI index in contrast to lender B with a market share of 20% that contributes a total of 400 points to the HHI index.

If lender A acquired Lender E and its market share increased 10 percentage points to 30%, the market went from unconcentrated to moderately concentrated with an HHI of 1,842 in Table 2 — the HHI increased 400 points. This is a significant increase in market share for Lender A and the agencies would mitigate the harms of this increase.

The HHI analysis also shows that mergers of banks with market shares that are not in the top three positions by market share can increase an HHI by amounts that exceed DOJ thresholds. In a hypothetical example at a metropolitan level, Lender D increased its market share by four percentages points after acquiring Lender H from Table 2 to Table 3 for a market share in Table 3 of 16%. The HHI increased by 96 points (just below the 100 point threshold) to 1,938 points.

If additional lenders beyond banks such as large fintechs are included in the HHI analysis, more situations of market concentration increasing beyond threshold levels would be captured. This would enable policymakers to enact more anti-trust and public benefit remedies. At the same time, considering non-banks would not preclude mergers of the smaller banks that may be seeking mergers in order to survive or increase their efficiencies. For example, if Lender I in Table 3 increased its market share from 3% to 4% from Table 2 to Table 3, the HHI would increase by 7 points, which is far below the DOJ thresholds (result of this merger not shown in the table 3).

Examples of HHI Analysis at a Metropolitan Level – Tables 1-3

Require Public Benefit Remedies when HHI Thresholds Exceeded

NCRC believes that HHI analysis should result in public benefit remedies in addition to anti-trust remedies. Currently, when a merger exceeds a DOJ threshold, the federal agencies might order branch divestures (typically, the merging banks will sell a specified number of branches). This might move the final HHI below the DOJ thresholds and preserve competition. However, it does not resolve convenience and needs concerns. In fact, the newly merged institution could use the branch divestitures as a pretext to decrease the level of lending, investing, and service to the community in contradiction to the convenience and needs factor in merger reviews.

In addition to anti-trust remedies, the thresholds must establish convenience and needs requirements. First, the agencies must institute conditional merger approvals for any highly concentrated market impacted by a merger regardless of the extent of HHI increases in those markets. The approval must order a public benefits remedy for the highly concentrated markets. These are markets that are already experiencing less competition and stagnation in terms of new and innovative products meeting emerging community needs. The stagnation is likely to worsen after the merger occurs. A public benefits remedy is needed to counter the stagnation and increase the responsiveness of banks to community needs.

Second, NCRC proposes that any merger approval that increases the HHI by 200 points and moves a market from unconcentrated to moderately concentrated levels must be accompanied by a conditional approval order. The order must require a concrete public benefit in any metropolitan area or rural county with HHIs exceeding the thresholds (see example above involving Table 2 in which an increase exceeding thresholds is accompanied by a significant 10-percentage point gain in market share). A concrete public benefit could be a community benefits agreement or a plan required by the agency that mandates specific improvements in CRA or fair lending performance measures.

In addition, an increase of an HHI of between 100 to 200 points in a moderately concentrated market would establish a presumption that an agency would require a public benefit improvement. While this threshold would not automatically result in a conditional merger approval mandating a public benefit requirement, it establishes a presumption of a public benefit requirement, particularly if the area is relatively underserved in terms of retail loans per capita or has major banks with mediocre or poor CRA and fair lending performance.

If a moderately concentrated market experienced an increase of between 100 to 200 points and it was underserved, the agencies should automatically require a public benefit. In recent white papers, NCRC has established a method for identifying underserved counties and census tracts based on measures involving retail loans per capita.[14] These papers divided either census tracts or counties in quintiles based on loans per capita. The lowest quintile of tracts and counties had the lowest median incomes, higher poverty levels and a higher percentage of people of color. The lowest quintiles of counties were concentrated in Appalachia, the South and the Midwest. The NCRC method of identifying underserved areas could be applied in cases of increases of 100 points in HHI. If the county is underserved (identified as being in the lowest quintile), the public benefit requirement automatically applies. If the county is not underserved but a certain portion of tracts (more than one third) are in the lowest quintile, the public benefit requirement automatically applies.

The public policy imperatives of adopting NCRC’s approach of underserved areas to merger review analysis is that it bolsters the implementation of the legal requirement of public benefit. It also identifies areas such as rural counties and communities of color that have been traditionally underserved and whose access to banking is most likely to decrease after mergers.

In addition to mandating public benefit improvements for markets that become concentrated, NCRC recommends a public benefit plan requirement for mergers when the combined assets exceed a specific size. These detailed plans would include performance goals, descriptions of products and how they are responsive to community needs, and explanations of how branch or other delivery systems would reach traditionally underserved populations. These plans must include ample time for public comment, a schedule for public updates on the progress of implementation and a mechanism for addressing instances where the financial institution is unable to meet performance goals.

Since consolidation has decreased lending in underserved communities over the last several years and since mergers are unlikely to slow down appreciably, a compensating mechanism would be rigorous public benefit plans specifying how lending, investing and bank service to underserved communities would increase after the mergers. Out of a total of about 6,000 banks, 139 have assets above $10 billion and 42 have assets above $50 billion. Applying a public benefits requirement to the largest banks of $10 billion or more would not be burdensome and would be appropriate since the most likely cutbacks in lending and service to communities would occur as a result of the largest mergers that do not have any follow-up accountability mechanisms.

The requirements for public benefit remedies discussed above that are triggered by HHI thresholds would apply to the geographical areas in which the thresholds were exceeded. In addition, a public benefits requirement must apply to mergers involving banks with the largest asset sizes. This requirement would entail banks addressing needs and developing performance measures applied to their entire geographical footprint.

The Legal Public Benefits Requirement Must be Implemented with Specific and Concrete Plans

The legal public benefits provision not only applies to mergers with potential anti-competitive impacts but to all mergers. Amending the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, the Bank Merger Act mandates that a federal bank agency shall not approve a merger transaction:

Whose effect in any section of the country may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly, or which in any other manner would be in restraint of trade, unless it finds that the anticompetitive effects of the proposed transaction are clearly outweighed in the public interest by the probable effect of the transaction in meeting the convenience and needs of the community to be served.

In every case, the responsible agency shall take into consideration the financial and managerial resources and future prospects of the existing and proposed institutions, the convenience and needs of the community to be served, and the risk to the stability of the United States banking or financial system.[15] (italics added)

The DOJ’s merger guidelines focus on anti-trust matters while the Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) guidelines also pay attention to the convenience and needs factor. The OCC’s Licensing Manual states, “The convenience and needs factor is distinguished from the CRA requirements in that the convenience and needs analysis is prospective, whereas the CRA requires the OCC to consider the applicant’s record of performance. The OCC considers any plans of the resulting, combined bank to close branches, particularly in low- or moderate-income areas, reduce services, or provide expanded or less costly services to the community.”[16] In its statement of policy, the FDIC states that it will consider how a merger would benefit the public through “higher lending limits, new or expanded services, reduced prices, increased convenience in utilizing the services and facilities of the resulting institution, or other means.”[17]

However, the banking agencies’ implementation of the public benefits or convenience and needs factor has been inconsistent and uneven. The merger review guidelines must be updated on an interagency basis involving the DOJ and the bank agencies with much more attention devoted to the convenience and needs factor. The statutory language states unambiguously that in every case, and especially in cases involving concentrated markets, the probable effect of the merger on convenience and needs must be considered.

The bank agencies typically review the most recent CRA exams of the merging banks in detail, but CRA exams consider past performance, not future or prospective performance. The statutory language requires a prospective analysis because merging banks undergo dramatic changes, which will impact their abilities to meet the convenience and needs of communities. These include structural changes involving the degree of centralized vs. decentralized decision-making that affects retail loan underwriting or decisions involving community development finance. NCRC member organizations have observed that when decisions become more centralized, communities distant from the bank headquarters will suffer declines in retail lending such as small business lending and/or decreases in complex community development financing for affordable housing or economic revitalization.

A concrete public benefits requirement counteracts the harm of any structural changes by committing the newly formed bank to improve upon its level of lending, investment and services consistent with banking law and the policy statements of the bank agencies. In contrast, most merger approvals over the last several years pay cursory attention to the convenience and needs factor. For example, the Federal Reserve Board approved Capital One’s takeover of ING Direct, an online bank, despite Capital One making vague promises in the convenience and needs section of its application. These promises included access that former ING customers would have to Capital One’s mortgage and small business loans. Within a few years, however, Capital One ceased making mortgage and small business loans and closed hundreds of branches in Texas and other states.

Occasionally, a federal bank agency will realize the public benefits standard by imposing a conditional merger approval. An example is the conditional approval of a merger involving Renesant Bank based in Mississippi. NCRC and our member organizations were concerned that the bank lagged its peers in the percentage of its loans made to minorities and low- and moderate-income borrowers and communities. The FDIC approved Renesant’s application to acquire Merchants and Farmers Bank conditional on a three-year plan to increase lending to underserved populations to match peer performance.[18]

Sometimes banks will commit to achieving public benefits voluntarily in the context of a merger approval process. KeyBank, as part of its acquisition of First Niagara, negotiated with NCRC and our member organizations a $16 billion pledge in loans and investments for underserved communities over a multi-year time period. This pledge was also motivated to help mitigate instances of concentrated markets, particularly in upstate New York and to compensate for the loss of products including a low down-payment lending program that had been offered by First Niagara in partnership with the Federal Home Loan Bank of New York.[19]

The agencies should prioritize certain public benefit remedies depending on the socio-economic conditions in the country. Currently, the national dialogue has focused on addressing systematic discrimination and racial wealth disparities. Policymakers have been discussing whether the Federal Reserve’s mandate under the Humphrey-Hawkins Act of 1978 to maintain low inflation and unemployment needs to be updated to address racial inequity. Recently, Federal Reserve Chairman Powell responded indirectly to this public dialogue by establishing a goal of tolerating higher inflation targets above 2% when warranted to increase employment and economic growth.[20]

The DOJ, Federal Reserve Board and other banking agencies must update their merger review process to address racial inequity. Merger approval orders mandating public benefits could establish goals and performance measures for people and communities of color in addition to LMI borrowers and communities. In communities where HHI thresholds require public benefit remedies, banks could also tailor specific community development lending and investing initiatives to address employment, health, educational or racial inequities identified by community residents and organizations generally and in comments during the public comment period on the merger.

Public benefit remedies must also address environmental inequities and those arising from the COVD-19 pandemic. The wildfires and hurricanes inflicted catastrophic damage across the country this summer, and these damages are greater in communities of color and LMI neighborhoods. NCRC recently released research finding that formerly redlined modest income areas and communities of color exhibit much higher incidences of diseases that make them more vulnerable to COVID.[21] Accounting standards that quantify the environmental impact of an institution’s loans and investments are starting to be developed and adopted by major financial institutions such as Morgan Stanley.[22] We encourage the agencies to evaluate how carbon accounting could also be factored into the evaluation of mergers and conditional approvals.

Banks could undertake a plethora of innovative community development projects under approval orders with public benefit mandates. For example, environmental redress could include clean-up and conversion of abandoned industrial sites, financing solar and renewable wind energy, home improvements that conserve energy and facilitate heating and cooling homes and erecting health clinics in LMI neighborhoods and communities of color. Recent interagency guidance on CRA has emphasized these types of projects to help communities recover from COVID.[23]

The agencies must significantly improve expectations and requirements concerning convenience and needs, particularly in merger approvals mandating public benefits. Vague promises in bank applications must be replaced by specific performance measures and goals for community development financing that responds to needs identified by community residents and organizations. Conditional merger approvals must likewise require annual public reporting regarding bank progress in meeting the goals and performance measures of the public benefits requirements.

As markets become more concentrated, it becomes difficult to rely solely on branch divestitures and other anti-trust remedies. The HHI thresholds then become more relevant in terms of public benefits remedies. In highly concentrated markets, for example, the agencies would need to order enormous numbers of branch divestitures, which would have uncertain impacts. Would price competition be improved significantly after the divestitures or would the impact on prices be minimal while the communities ended up experiencing reductions in lending and banking services if the lenders acquiring the branches did not have as much capacity to offer services as the sellers? This suggests that it might be impractical to unwind large banks in some markets through massive branch divestitures. The public benefits requirement must then be automatic as discussed above.

Answers to Questions Posed by DOJ

In this section, NCRC answers the specific questions posed by the DOJ in its request for comment. Our answers build on our above analysis and our assertion that both anti-trust analysis and analysis of convenience and needs must be bolstered:[24]

Guidance Generally

- Interagency guidance – Above, NCRC makes the case that interagency guidance needs to be more robust in terms of the convenience and needs factor in merger reviews and needs to institute public benefits mandates when the HHI exceeds certain thresholds and in mergers exceeding asset size thresholds.

HHI Thresholds- Updating 1995 Banking Guidelines with 2010 Horizontal Merger Review Guidelines

- HHI increases of 100 points – Increases of the HHI index of 100 points resulting in moderately concentrated markets is part of the 2010 Horizontal Merger Review and would be a good addition to the 1995 merger guidelines.[25] As discussed above, an HHI can increase 100 points when a bank increases its market share by four percentage points, which is a significant increase in market share. Moreover, as discussed above, since consolidation has increased substantially in the last couple of decades, HHI thresholds must be lowered since anti-competitive markets are more likely. Stagnation in price competition and less innovation in product development stifles community development, particularly in underserved communities.

- Stable market shares – The 2010 merger review guidelines indicate that stable market shares should heighten the possibility of additional anti-trust reviews. This is a good indication of a lack of robust competition that should be incorporated into the 1995 banking guidelines.

Relevant Product and Geographic Markets

- HHI analyses for separate products: In addition to the products listed in the DOJ question, NCRC suggests that home lending and small business lending must be evaluated separately by HHI analysis. Current HHI analysis, as discussed in Federal Reserve Board merger approval orders, usually considers deposits only. This sole focus is becoming less relevant to assess accurately levels of market concentration. It results in underestimations of market concentration when thrifts and credit unions are weighted at less than 100 percent. Thrift and credit unions could have larger loan than deposit market shares; deposit market share analysis will therefore underestimate market concentration.

This is also particularly true in the home lending market in which non-banks now have a larger overall market share than banks, as shown by recent NCRC research.[26] Finally, small business market analysis must also incorporate non-banks and fintechs since these lenders now have a substantial market share, as discussed above. The DOJ and federal bank agencies should consider routinely conducting the three product market analyses of deposits, home lending and small business lending. They can then weight the final HHI score, depending on the type of merger contemplated. If the merger features large-scale home lenders, for example, the home loan market analysis would be weighted at 50% or more since the merger’s impact would be greatest in the home loan market.

The procedures of weighting credit unions and thrifts at less than 100% should cease upon regular implementation of multi-product market HHI analysis. This is a crude estimation procedure that will result in inaccurate portrayals of the actual extent of market concentration.

The agencies must also work with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) to finalize a robust rule implementing Section 1071 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. Section 1071 could be a vast improvement upon the CRA small business loan data and the call report data only if it comprehensively covers banks and non-banks. Robust Section 1071 data is indispensable for accurate HHI analyses.

Deposit data collection must be improved. A Question and Answer (Q&A) document (see Question 26) maintained by DOJ states that internet-bank deposits are currently not included in HHI analysis since data is not collected on the geographical location of deposits obtained via non-branch means.[27] It would seem that it is feasible to collect the geographic location of customers with deposit accounts since customer addresses can be geocoded to census tracts and counties.

HHI analyses should also be performed for consumer lending and payments. The agencies would need to institute data collection requirements for these products. The public interest needs to be safeguarded in these markets as well.

- HHI analysis for geographical markets: As a baseline, the HHI analysis on a metropolitan level and on a county level for rural counties is sufficient. However, the DOJ Q&A document in Question 29 indicates that DOJ does not have pre-defined markets, unlike the Federal Reserve and will review the competitive impacts of the merger on a case-by-case basis.[28] Maintaining flexibility in HHI analysis is imperative. Within a metropolitan area, for example, different counties may experience significantly different banking markets. An urban core county could be underserved compared to suburban counties, as identified via the NCRC analysis discussed above. Thus, within this metropolitan area, the DOJ would want to analyze separately the HHI impact for the underserved county. Also, the DOJ and the agencies may want to consider separate HHI analyses for LMI tracts and communities of color, particularly those in geographical areas that analyses similar to NCRC’s identify as underserved.

- Analysis of Consumer and Banking Products Must be Local: The DOJ must not consider or incorporate in any manner HHI analysis on a state, regional or national level. Despite advances in technology, banking remains a local matter. FDIC research has shown that large portions of the population continue to rely on branches. LMI customers and small businesses also depend on branches, particularly for larger and more complex transactions such as home or small business loans.[29] Prices of products and access to products that respond to local demographics and market conditions continue to vary across metropolitan areas and counties. Any state, regional or national HHI analyses will gloss over these dynamics and would likely under-estimate the level of market concentration. When markets are more concentrated on a local level, not only would prices be higher, but the institutions will also be less responsive to tailoring their products to local needs and conditions.

HHI Analysis for Urban and Rural Markets

- Geographical areas: As stated above, rural HHI analysis should be conducted at a county level. Urban HHI analysis can be conducted at a metropolitan level unless the metropolitan area has underserved counties, which should be separately analyzed.

- Need for a white paper: The DOJ should produce a white paper reviewing current concentration levels in urban metropolitan areas, urban counties, rural counties and underserved counties and census tracts. The DOJ should also assess the stability of urban compared to rural markets. If rural markets are more stable, this would be an indication of less entry and exit and consequently, less robust competition. Analyzing the market share of the top five or six financial institutions across various products in urban and rural areas would also lend insight in the robustness of competition and the need to lower HHI thresholds for any set of areas. A 45-day public comment period is insufficient time for members of the public to conduct the comprehensive research needed to assess whether different HHI thresholds are needed in urban and rural areas.

- Farm lending needs to be separately considered: Farm lending and farm credit should not be considered a mitigating factor but should be separately analyzed as a distinct product in an HHI analysis. Small business loan markets for micro-businesses such as service sector businesses are quite different from small farm loan markets. One immediate difference is the large differences in collateral. Farmers own buildings and fields, while service-sector firms would lack this type of collateral. Therefore, market dynamics and the number of firms serving both markets are likely to be different. These differences would be obscured by HHI analyses combining these product markets.

Non-Traditional Banks Should be Included

- Inclusion of non-traditional banks: As stated above, non-banks should be included in HHI analysis. Since they do not receive deposits, the HHI analysis including them would be home or small business lending analysis. Concentration levels would probably be underestimated in any HHI home or small business loan analysis omitting large-scale non-bank lenders.

- Deposits of online banks: The question about DOJ’s consideration of online bank deposits is puzzling since DOJ does not currently consider these deposits as stated above. NCRC recommends that data collection efforts need to be improved so that deposits of online lenders can be included in HHI analyses.

- Credit unions and thrifts: As stated above, the weighting of credit unions and thrifts at less than 100% is a relic of HHI analyses that only consider deposits. This practice should be discarded, and instead separate HHI analysis of home lending and small business lending should be conducted as well. The total impact of credit unions and thrifts on the market can be better captured if the separate product analyses are conducted.

- Incorporating online banks into HHI analysis: As the question states, online bank deposits cannot be currently used in HHI analysis. The agencies should change their regulations, such as CRA regulations to require geocoding of online deposits. Until this is done, some online banks will have home loan or small business loan data that can be incorporated in the separate HHI analysis of home and small business lending recommended by this comment letter.

De Minimis Exception

- DOJ should not create de minimis exceptions allowing the agency to skip anti-trust analysis for smaller bank mergers. Smaller mergers can occur in highly concentrated markets that would need scrutiny. Moreover, once any exception like this is created, pressure will build on the agency to expand these exceptions in future years.

Conclusion

Merger reviews conducted by DOJ and the federal bank agencies must increase the rigor of their anti-trust and convenience and needs reviews. HHI thresholds need to be lowered that trigger not only anti-trust remedies but also public benefit remedies for moderately and highly concentrated markets. The largest mergers must be accompanied by public benefit plan requirements.

Consolidation has increased significantly over the last couple of decades. Rather than a force for more competition, technology has probably contributed to the consolidation and so far has not materially increased lending and investing for underserved communities. The invisible hand of market forces will deliver invisible benefits in this era of consolidation. Only a robust regime of public benefit plan requirements and anti-trust rigor will introduce the market transparency needed that will clearly benefit communities of color and LMI communities as they recover from COVID-19.

If you have any questions, please contact me or Josh Silver, Senior Advisor, on 202-628-8866 or jvantol@ncrc.org or jsilver@ncrc.org.

Sincerely,

Jesse Van Tol

CEO

The undersigned organizations support the positions in this letter:

National

Consumer Action

National NeighborWorks Association

Small Business Majority

Alabama

NAACP Economic Programs

Arizona

Pima County Community Land Trust

California

EAH Housing

Peoples’ Self-Help Housing

Self-Help Enterprises

Colorado

Urban Land Conservancy

District of Columba

Revolving Door Project

Florida

Affordable Homeownership Foundation, Inc.

Community Reinvestment Alliance of South Florida

Florida Housing Coalition

Georgia

Veterans Center of Greater Atlanta

Hawaii

Hawai’i Alliance for Community-Based Economic Development

Illinois

Housing Action Illinois

Woodstock Institute

Indiana

Continuum of Care Network NWI, Inc..

Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana, Inc.

Northwest Indiana Reinvestment Alliance

Kentucky

REBOUND, Inc.

Louisiana

Cenla Housing Alliance

Greater New Orleans Housing Alliance (GNOHA)

Housing 1st Alliance of the Capital Area

HousingLOUISIANA

HousingNOLA

Libery Restoration CDC

Mid City Redevelopment Alliance

Modern Media Barn

Maryland

Maryland Consumer Rights Coalition

Mississippi

Housing Education & Economic Development (HEED)

North Montgomery Citizens United for Prosperity (MCUP)

Missouri

Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing and Opportunity Council

New Jersey

New Jersey Citizen Action

New York

Fair Finance Watch

NYS Rural Housing Coalition

North Carolina

Community Link Programs of Travelers Aid Society of Central Carolinas Inc.

Henderson and Company

Oregon

Housing Oregon

JOVIS

NeighborWorks Umpqua

Pennsylvania

African Cultural Alliance of North America Inc. ( ACANA )

Rhode Island

HousingWorks of RI

Texas

City Wide Community Development Corporation

Ministrie Impact CDC

Southern Dallas Progress Community Development Corporation

[1] Current Use of Mobile Banking and Payments, Federal Reserve Board, see Table 4, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/mobile-devices/2012-current-use-mobile-banking-payments.htm and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, 2017, https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2017/2017report.pdf, see pp. 27 & 32.

[2] Comment letter of Jeremy C. Kress, Assistant Professor of Business Law, Senior Research Fellow, Center on Finance, Law & Policy, University of Michigan.

[3] Amy G. Lorenc & Jeffery Y. Zhang, The Differential Impact of Bank Size on Systemic Risk 12-18 (Fed. Reserve Bd. Fin. & Econ. Discussion Series, Working Paper No. 2018-066, 2018), https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2018066pap.pdf

[4] Institute for Local Self Reliance, Number of Banks in the United States, https://ilsr.org/number-banks-u-s-1966-2014/

[5] Robert Adams and John Driscoll, How the Largest Bank Holding Companies Grew: Organic Growth or Acquisitions?, FEDS notes, December 2018, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/how-the-largest-bank-holding-companies-grew-organic-growth-or-acquisitions-20181221.htm

[6] Jason Richardson and Jad Edlebi, Preliminary Analysis Of 2019 HMDA Mortgage Lending Data, June 2020, https://www.ncrc.org/preliminary-analysis-of-2019-hdma-mortgage-lending-data/

[7] Cole, R.A., L.G. Goldberg, and L.J. White. 1999. Cookie-Cutter versus Character: the Micro Structure of Small Business Lending by Large and Small Banks, in J.L. Blanton, A. Williams, and S.L.W. Rhine, ed.: Business Access to Capital and Credit (Federal Reserve System Research Conference, March 8, 1999). Cavaluzzo, K.S., L.C. Cavaluzzo and J.D. Wolken. 2002. Competition, Small Business Financing, and Discrimination: Evidence From a New Survey. Journal of Business. January 2002, vol. 75, no.4

[8] Stacy Mitchell, Access to Capital for Local Businesses, institute for Local Self Reliance, https://ilsr.org/rule/financing-local-businesses/

[9] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Small Business Credit Survey, https:\www.newyorkfed.org\smallbusiness\small-business-credit-survey-2020

[10] NCRC, Access To Capital And Credit For Small Businesses In Appalachia, May 2007, https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2007/05/ncrc%20study%20for%20arc.pdf and NCRC Access To Capital And Credit In Appalachia And The Impact Of The Financial Crisis And Recession On Commercial Lending And Finance In The Region, for the Appalachian Regional Commission, July 2013, https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/accesstocapitalandcreditInappalachia.pdf

[11] Immergluck, D. and G. Smith. Bigger, Faster…But Better? How Changes in the Financial Services Industry Affect Small Business Lending in Urban Areas. Woodstock Institute, September 2001

[12] Josh Silver, The Importance Of CRA Assessment Areas And Bank Branches, June 2018, NCRC, https://ncrc.org/the-importance-of-cra-assessment-areas-and-bank-branches/

[13] DOJ Horizontal Merger Guidelines, 2010, Section 5.3 Market Concentration.

[14]Josh Silver and Bruce Mitchell, PhD, How to Consider Community Development Financing Outside of Assessment Areas by Designating Underserved Counties, NCRC, January 2020, https://ncrc.org/how-to-consider-community-development-financing-outside-of-assessment-areas-by-designating-underserved-counties/ and Bruce Mitchell, PhD. and Josh Silver, Adding Underserved Census Tracts As Criterion On CRA Exams, NCRC, January 2020, https://ncrc.org/adding-underserved-census-tracts-as-criterion-on-cra-exams/

[15] See the FDIC webpage section on the Federal Deposit Insurance Act, specifically Section 18(c)(5)(B) via https://www.fdic.gov/ regulations/laws/rules/1000-2000.html

[16] Comptroller’s Licensing Manual, Public Notice and Comments, Version 1.1. November 2017, https://www.occ.treas.gov/publications/publications-by-type/licensing-manuals/file-pub-lm-public-notice-and-comments.pdf ,p.9.

[17] See https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/5000-1200.html

[18] FDIC Approval Order available from NCRC upon request. The FDIC archive of approval orders has not been updated for a number of years. See https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/bankdecisions/merger/index.html#R

[19] See a summary of KeyBank’s benefits agreement on http://www.ncrc.org/media-center/press-releases/item/1120-ncrc-andkeybank-announce-landmark-$165-billion-community-benefits-agreement

[20] Chair Jerome H. Powell, New Economic Challenges and the Fed’s Monetary Policy Review, August 2020, Federal Reserve Board, https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20200827a.htm

[21] Redlining and Neighborhood Health, September 2020, NCRC, https://ncrc.org/holc-health/

[22] ” Morgan Stanley Joins Leadership of Global Carbon Accounting Partnership.” Morgan Stanley Press Release. July 20, 2020. Available online at https://www.morganstanley.com/press-releases/morgan-stanley-joins-leadership-of-global-carbon-accounting-part

[23] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Joint Statement on CRA Consideration for Activities in Response to COVID-19, March 2020, https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/caletters/CA%2020-4%20Attachment.pdf

[24] DOJ, ANTITRUST DIVISION BANKING GUIDELINES REVIEW: PUBLIC COMMENTS TOPICS & ISSUES GUIDE, https://www.justice.gov/atr/antitrust-division-banking-guidelines-review-public-comments-topics-issues-guide?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

[25] DOJ Horizontal Merger Review Guidelines.

[26] NCRC, Preliminary Analysis Of 2019 HMDA Mortgage Lending Data, op. cit.

[27] How do the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division, analyze the competitive effects of mergers and acquisitions under the Bank Holding Company Act, the Bank Merger Act and the Home Owners’ Loan Act? FAQshttps://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2014/10/09/308893.pdf?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

[28] Interagency FAQs

[29] Josh Silver, The Importance Of CRA Assessment Areas And Bank Branches, June 2018, NCRC, https://ncrc.org/the-importance-of-cra-assessment-areas-and-bank-branches/